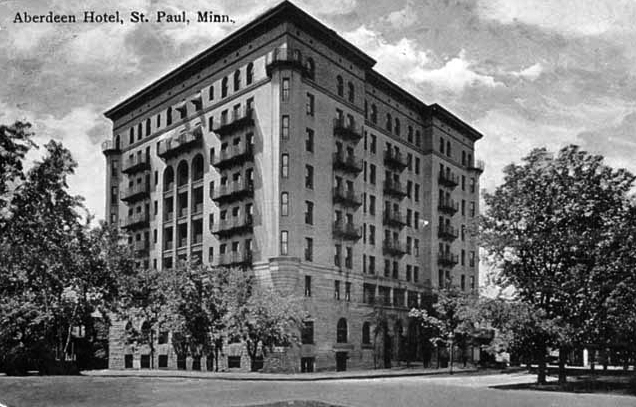

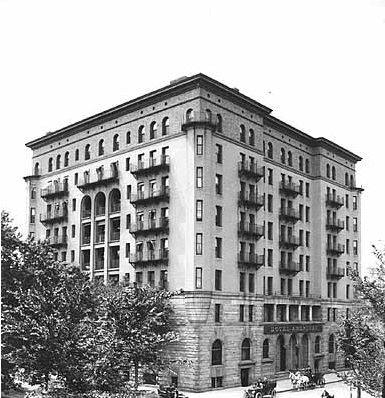

Aberdeen Hotel: The Grandest Apartment Hotel in St. Paul

The Aberdeen Hotel may not have been the first luxury apartment hotel in the Twin Cities, but it was undeniably the grandest of them all. Constructed in 1889 for $250,000, the hotel was located just three blocks from St. Paul’s exclusive Summit Avenue and catered to a well-heeled clientele seeking the comforts of home without the annoyance of keeping house. Governor John A. Johnson called the hotel home from 1904 to 1910, and St. Paul Cathedral architect Emmanuel Masqueray lived at the Aberdeen for several years. The main floor of the hotel featured an opulent lobby and a grand ballroom. The café offered meals by request for residents and visitors in an elegant dining room.

Fourteen of the hotel’s units were available as single rooms for travelers, while the other seventy-eight were arranged as two- to eight-room residential suites that could include a reception room, kitchen, pantry, dining room, library, and a balcony. Every unit in the hotel had a private bath, which was not a common amenity at the time. For five dollars per night, two dollars more than any other hotel in St. Paul, the Aberdeen offered guests every possible convenience for comfortable family living.

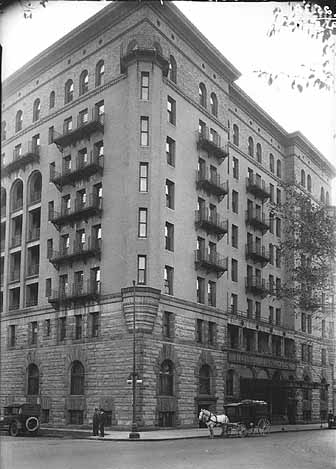

As it aged, the hotel began to lose its footing as a luxury residence. After World War I the federal government saw an opportunity to turn the hotel into a hospital for returning veterans. The United States Veterans Bureau leased the hotel until March 1927, when patients were moved to a brand new facility near Fort Snelling.

The Aberdeen was sold at auction for $750 but remained vacant after the sale. During the Great Depression, the hotel was bought and sold several times over, often changing hands two or three times per year. No one seemed able to put the old hotel to good use. In 1937, the Aberdeen Hotel was the site of the gruesome murder of Ruth Munson, a thirty-year-old waitress whose body was found in the hotel after a fire on the second floor. Police noted that the empty rooms and hollow hallways echoed every breath and footfall, and the thick walls and dusty gray windows hid everything that happened inside, making it an ideal site for criminal activity.

After Munson’s murder, the community was horrified that something so horrible could happen in their neighborhood. Perhaps as a way to erase what happened in the hotel that December night, residents pressured the City of St. Paul to have the derelict hotel condemned and demolished. In 1944, the once-prestigious hotel fell to the wrecking ball. As if trying to redeem itself, the demolished hotel yielded over five tons of scrap iron for the war effort.

Today, a parking lot and the YWCA occupy the site.