Wonderland Amusement Park’s Glass Castles

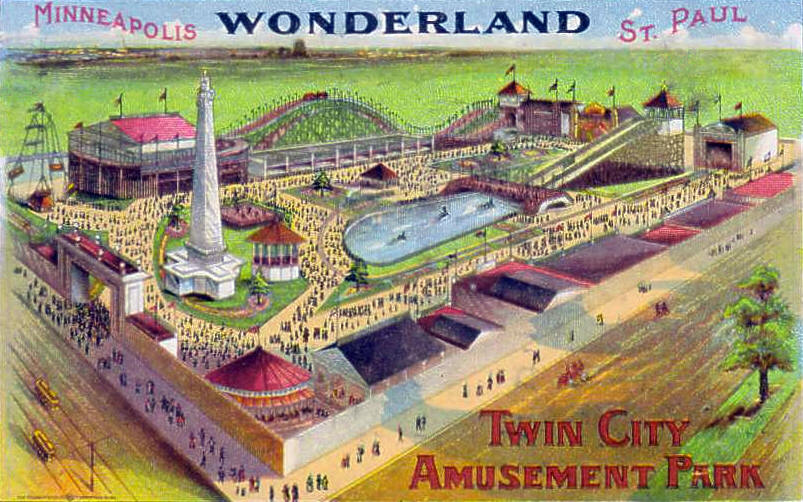

At the turn of the 20th century, urban amusement parks were a popular form of communal entertainment. Throughout the country, parks modeled after Coney Island in New York were popping up in most major cities. Attractions varied from city to city, but most featured a roller coaster, carousel, an aerial swing for thrill-seekers, a dancing pavilion for couples and teenagers, flower gardens and picnic spaces for families, and an electrically lit tower that could be seen for miles to guide crowds to the park. Minneapolis’ version of Coney Island was the Twin City Wonderland amusement park–“a family resort with the pleasures of ladies and children as the direct object.” Intoxicating beverages, bawdy cabarets, and sideshow acts were not found at Wonderland. What it did have, however, was one of the first infantoriums in the nation.

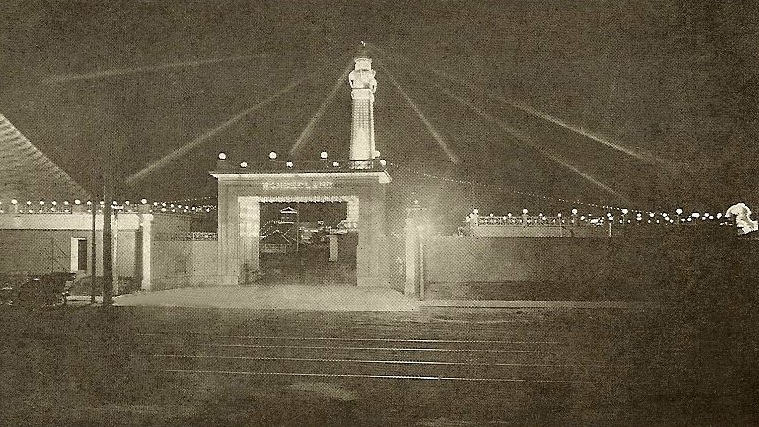

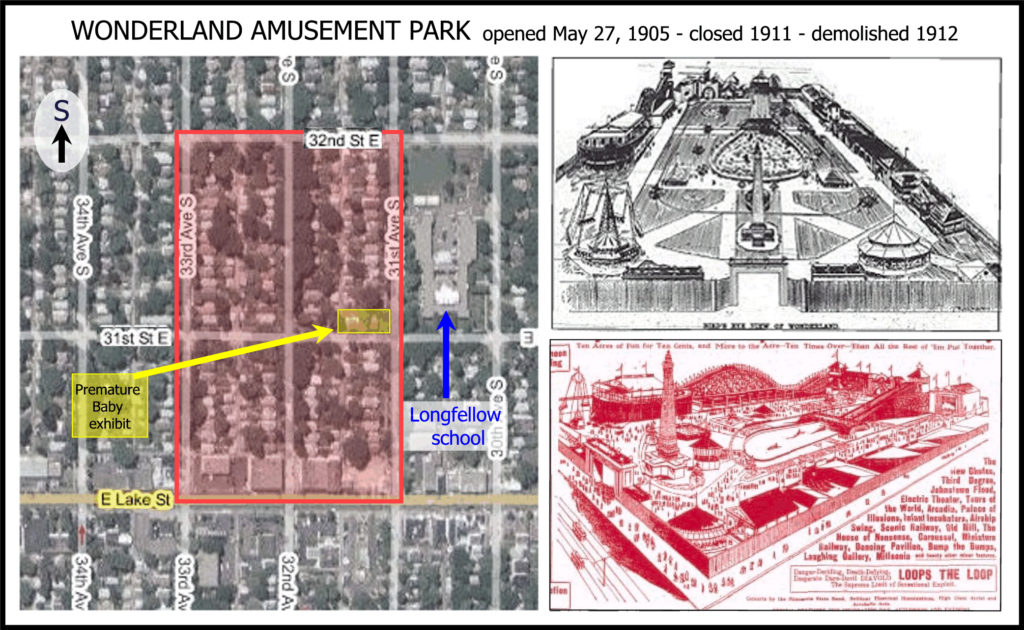

When Wonderland opened in 1905, it was big news. Minneapolitans could take the streetcar to 31st and Lake Street and walk through the grand gates into another world. Over a half-million people came to the park that first summer. Its biggest draw was the infantorium, a scientific exhibit showing a modern method for saving premature babies. For 10 cents, visitors could enter the two-story building at the far end of the park to marvel at the tiny babies in shiny steel-framed incubators with glass sides. Most of the money collected from admission was put right back into the facility. It paid for supplies the babies needed, physicians and nurses who were specially trained in Paris or Berlin to work with the tiny babies, and the electricity it took to keep the incubators running non-stop. The facility cared for any premature baby that was referred by a physician, regardless of socioeconomic or racial background and at no cost to the parents.

Inside these little glass castles, each baby was wrapped in a fleece-lined robe made especially for them by French nuns. The robes were tied with pink or blue ribbons to distinguish girls from boys, and each baby had an identification necklace to prevent the staff from returning a baby to the wrong family when he or she was ready to go home. The filtered air, regulated temperatures, strict hygiene, and adequate nutrition the babies received at the facility kept them alive at a time when the mortality rate for premature babies was close to 65%.

Since most children born in this era were born at home, premature babies were typically brought to hospitals that could not provide quality care for them. Even in the best hospitals, half of all infants under one year of age died after being treated. The survival rate was exceptionally lower if the baby was cared for at home. However, the Wonderland facility boasted an 88% survival rate.

Wonderland closed its gates in 1911 after consecutive years of bad weather and slow ticket sales, but the legacy of the infantorium lived on. The exhibit, and others like it across the country, created an impact by exposing Americans to a technology they would otherwise never have seen. The facilities played a key role in the transition to caring for premature infants in hospitals and led to better care of premature infants at home by giving people the opportunity to see how the infants were cared for in hospitals.

The amusement park was demolished in 1912 and most of its rides were relocated to the Excelsior Amusement Park on Lake Minnetonka. Perhaps fittingly, the only piece of Twin City Wonderland that was spared from demolition was the building that housed the tiny babies in their glass castles. It was converted to apartments and still stands on the southeast corner of 31st Avenue and 31st Street.