Elizabeth Quinlan’s Renaissance Revival Palace

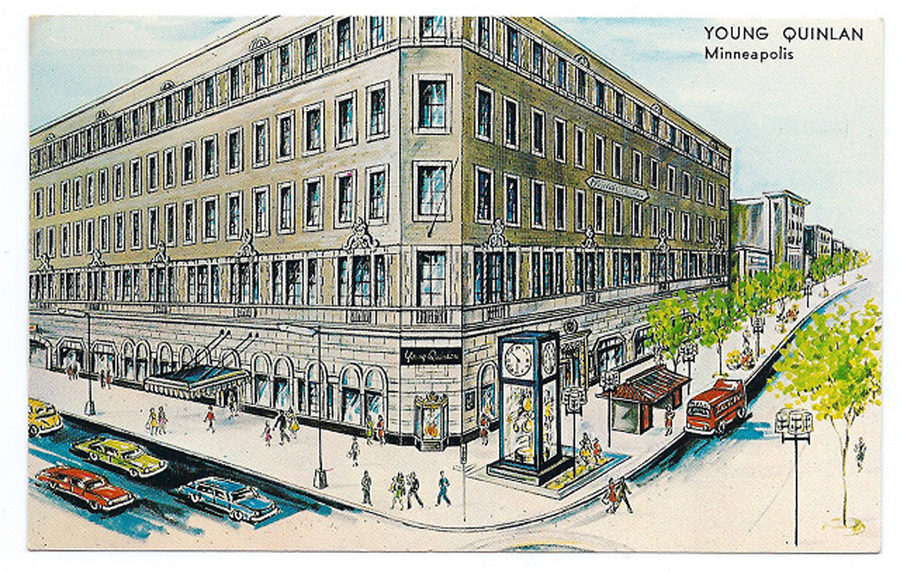

Elizabeth C. Quinlan was the co-founder of the Young-Quinlan Department Store in downtown Minneapolis. The popularity of her store was due in large part to offering exceptionally-made clothing and accessories to not only the elite women of Minneapolis, but also to the middle class. The lower cost of ready-to-wear clothing meant that middle-class women could buy off the rack thus having more than a handful of outfits for each season and a quick and easy way to obtain the latest fashions. Quinlan’s enormous success enabled her to do many things that most women during this time could not. At the height of her success, she built a beautiful home for herself and her sister, Annie.

Their Minneapolis home would become a top address on the Twin Cities movers-and-shakers circuit. After their mother’s death in 1914, the Quinlan sisters lived in rented apartments, including 1770 Hennepin Avenue and The Leamington–a swish residence hotel at 10th and Third Avenue S. Annie, who owned the corset shop at Young-Quinlan, and Elizabeth decided to build a comfortable home for themselves in the prestigious Lowry Hill neighborhood of Minneapolis. Together, they purchased two-and-a-half city lots on Emerson Avenue S and set about finding an architect to build their dream home. Elizabeth knew New York architect Frederick Ackerman through his wife. Ackerman was a Cornell graduate who studied architecture in Paris for two years before earning a reputation for building beautifully private country residences.

In 1923, Elizabeth set him on the task of designing her a home reminiscent of the 16th-century villas she had seen while traveling in Florence, Italy. Their home would eventually serve as an architectural prototype for the new Young-Quinlan store, also designed by Ackerman. Both sisters had significant input on the design of their home, but Elizabeth—a perfectionist by nature—exchanged many letters with Ackerman about her tastes and preferences in the design. On her business trips, she would often tour homes or visit the studios of craftsmen in New York and Europe under Ackerman’s suggestion. By December 1923 the plans were complete and building at 1711 Emerson Avenue S would start soon after.

Completed in 1924 at a cost of $47,000, Annie and Elizabeth’s three-story Italian Renaissance Revival home was the toast of the town. It was originally built as a duplex to house Annie and Elizabeth in the two-level, 4,560 square-foot upper unit, and their niece—Elizabeth Butterfield in the 2,260 square-foot, main floor unit. After Butterfield’s death, the sisters rented out the main floor unit to a well-heeled tenant. A 1,160 square-foot basement added room for storage and laundry facility for both units.

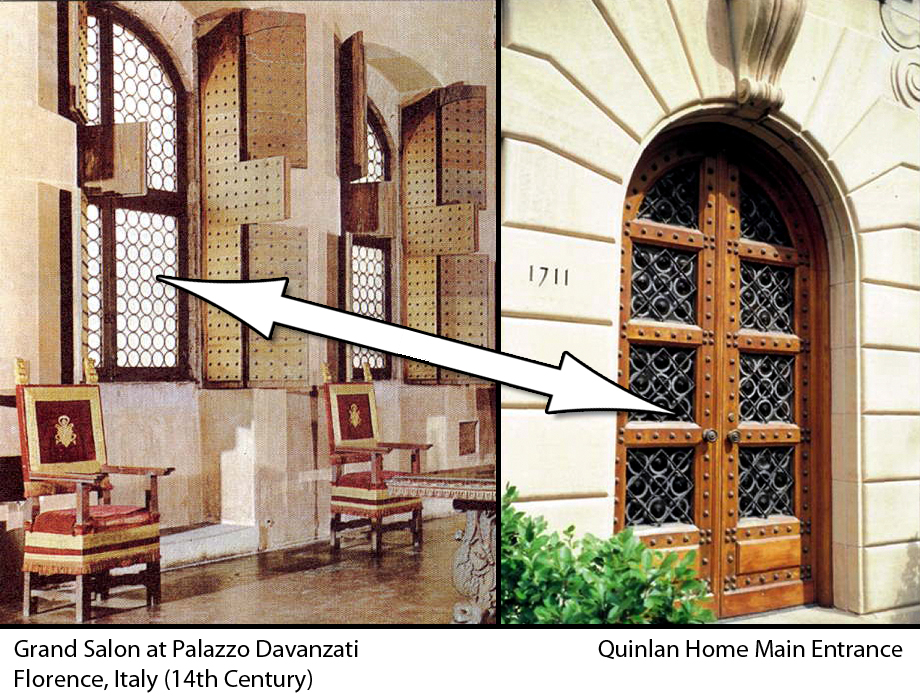

The L-shaped, stucco home with a terra-cotta tiled roof was a breath of fresh air in a neighborhood filled with the very traditional brick homes that old Minneapolis money preferred. However, the Quinlan home stood equal to all of the others in luxury. The main entrance featured an arched oak-framed double door with a monumental surround. Each door had four panels filled with amber Belgian glass discs. The glass discs were overlaid with iron grillwork to give it a rustic look. All of the windows had sills of marble and were flanked by louvered wooden shutters. French windows appeared on the second level — each featured an intricate wrought-iron balcony. Copper gutters and downspouts carried water from the roof to the ground in style.

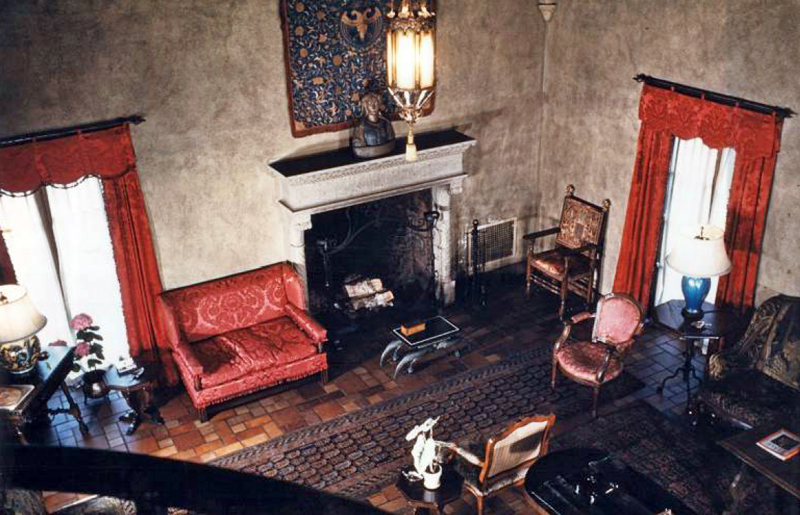

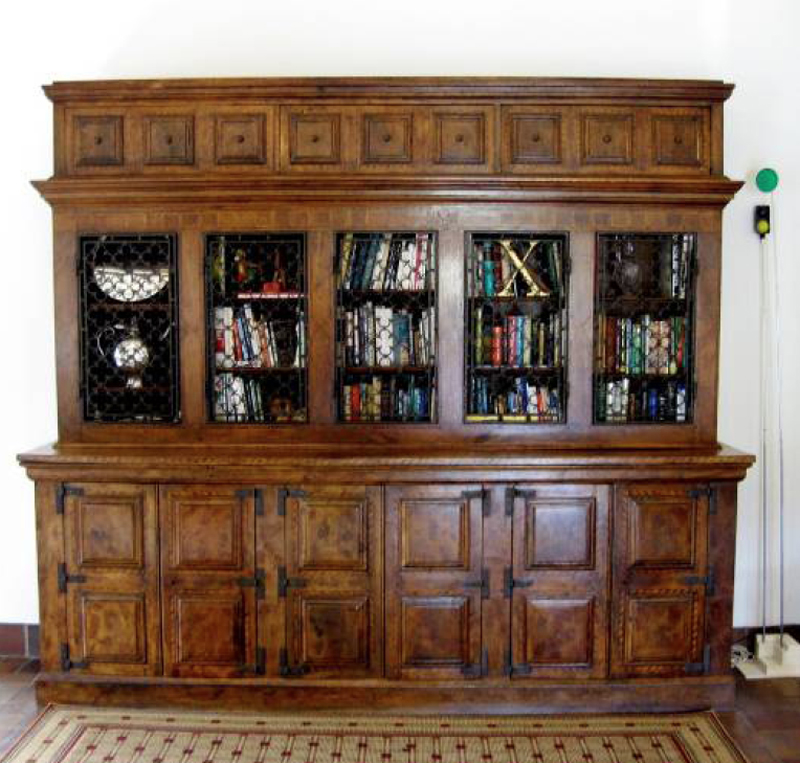

Once inside, visitors could choose to enter the lower unit by way of a large oak door in the entry vestibule or ascend the circular stone and wrought-iron staircase to the upper unit. At the top of the stairs, a pair of wrought-iron gates—fabricated for Quinlan by the Michelozzo Gallery in Florence—gave entrance to Annie and Elizabeth’s home. The walls and ceiling of the living and dining rooms were covered in sand float plaster to give the rooms the rusticated appearance of a 16th-century Italian villa. A Corinthian-style column separated the living room from the dining room. All of the woodwork was birch stained light walnut. Quarry floor tiles in various shades of brown added to the rustic look. In the living room, a large fireplace of Mankato bluff stone with a travertine mantle stood opposite the wrought-iron entry gates. The design of a large monastery cabinet in the living room was based on a historic piece Elizabeth saw in the Palazzo Davanzati in Florence. Just off the living room was a striking Art Deco style powder room for guests. The walls were decorated with curves, stripes, and strange species of colorful garden flowers. All of the woodwork was painted silver, and a sleek dressing table was lit through opaque glass surfaces. A half-moon mirror hung above the table. Adjacent to the dressing table stood an elegant sink with a carved marble and stone basin sitting atop a sculpted swan pedestal. Bronze dolphin fixtures complimented the design. The rest of this floor featured a large kitchen and pantry, extra closet space, and two bedrooms for the help.

The third floor was accessed by a stairway near the living room. This level housed Annie and Elizabeth’s bedrooms and featured vaulted ceilings and hardwood floors throughout. Both bedrooms each had a closet and dressing room, a private bath, and a curved-front fireplace with a Quinlan family crest cartouche on the wall above the mantle. Elizabeth’s bathroom was decorated in Art Deco style with underwater scenes of fishes and seaweed. Adjacent to her bathroom was her dressing room, also decorated in the Art Deco style. The walls were covered in mirrors and decorated with woodland elves and nymphs. A dressing table with an illuminated glass surface dominated the room. There is no documentation about how Anne’s rooms were decorated. A third bedroom and bathroom on this level were frequently used by houseguests.

The Quinlan’s Italian-inspired home was a fitting place to display Elizabeth’s collection of Renaissance-era antiques. Most notably, the living room exhibited an enormous Gobelins (Flemish) Renaissance tapestry, a 17th-century Italian divan, an Egyptian prayer rug, and red draperies from the home of a former Sicilian Cardinal. A 16th-century vargueno chest stood in the dining room. Elizabeth’s bedroom housed a prie-dieu that some documentation has credited to the “Countess of Toledo”, but my research has found that no such person ever existed. I believe this prie-dieu came from the estate of Eleanor of Toledo, a Spanish noblewoman who was the Duchess of Florence from 1539 and is credited with being the first modern first lady, or consort. She served as regent of Florence during the absence of her husband.

Annie and Elizabeth Quinlan lived together in their upper duplex from 1924 until their deaths; Annie in 1946 and Elizabeth the following year. Upon her death, the majority of Elizabeth’s assets passed to The Elizabeth C. Quinlan Foundation. The Foundation chose to Elizabeth and Anne’s home to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. The MIA sold it back to a private buyer in 1981. It remains a private residence today with many of the important architectural features still intact. The home is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.