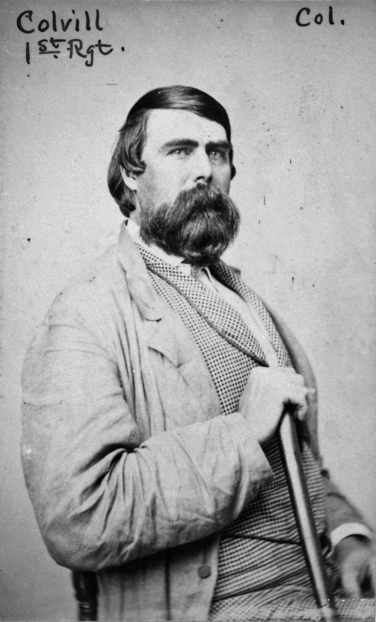

Colonel Colvill of the First Minnesota

William Colvill — does that name ring a bell? Unless you’re a Civil War history buff, this name probably doesn’t mean anything to you yet. Perhaps he’s been forgotten because he was a good, simple man — hard-working and generous. He held fast to what he believed was right and stood up against wrongdoing. Perhaps it’s only natural for his name to fade into obscurity after so many years, he probably would have preferred that anyway. But let’s not let that happen just yet. William Colvill deserves to be remembered.

An often overlooked bronze statue of William Colvill currently stands in the rotunda of the Minnesota State Capitol. Thousands of people pass but it each year, yet most probably never stop to wonder who Colvill was or why he has a place of such prominence in the Capitol. However, this statue is an exact reproduction of another that is more difficult to overlook. The original statue stands proudly in the Cannon Falls Community Cemetery where Colvill is buried. It towers over all of the other graves from a shady hill near the eastern edge of the cemetery.

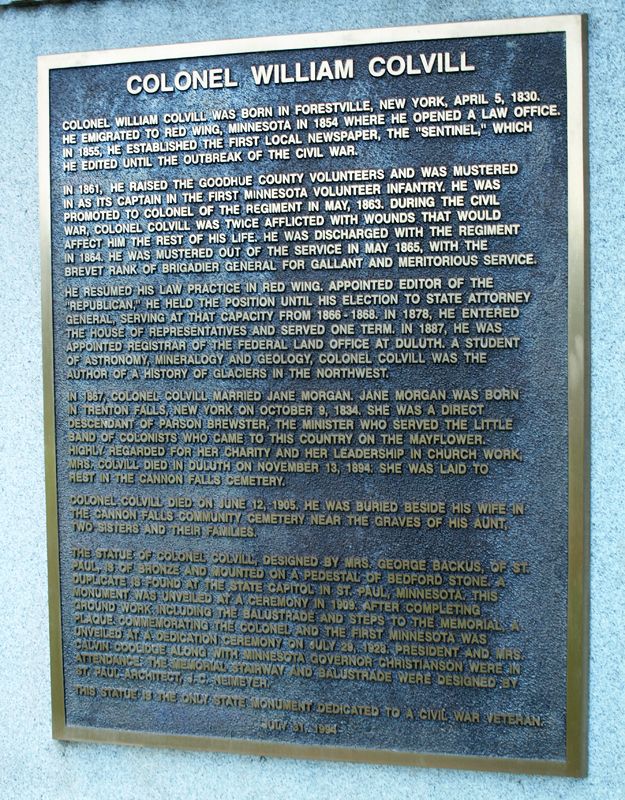

Colvill arrived in Red Wing by steamboat in 1854, he was 24 years old. Born in Forestville, New York, he studied law in Buffalo under Milliard Fillmore. Fillmore would go on to become the thirteenth President of the United States. Once his education was complete, Colvill moved back to his hometown where he practiced law for several years. He dreamed of moving west and decided the Minnesota Territory would be a good match for him.

Like so many pioneers, he held several jobs in Red Wing. He had his own law practice, was the county clerk, and owned shares in the local newspaper, the Red Wing Sentinel, where he was also the sole editor. He relinquished his shares in the paper in 1860 due to differing political opinions at the newspaper.

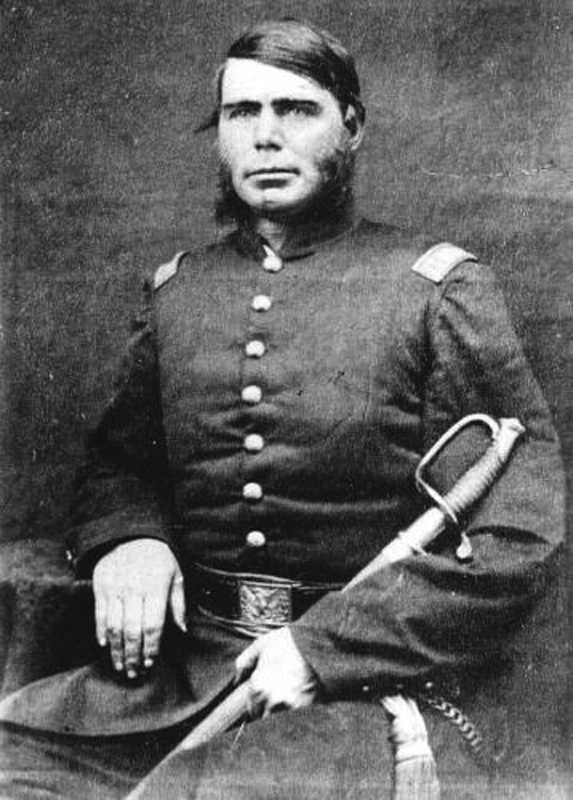

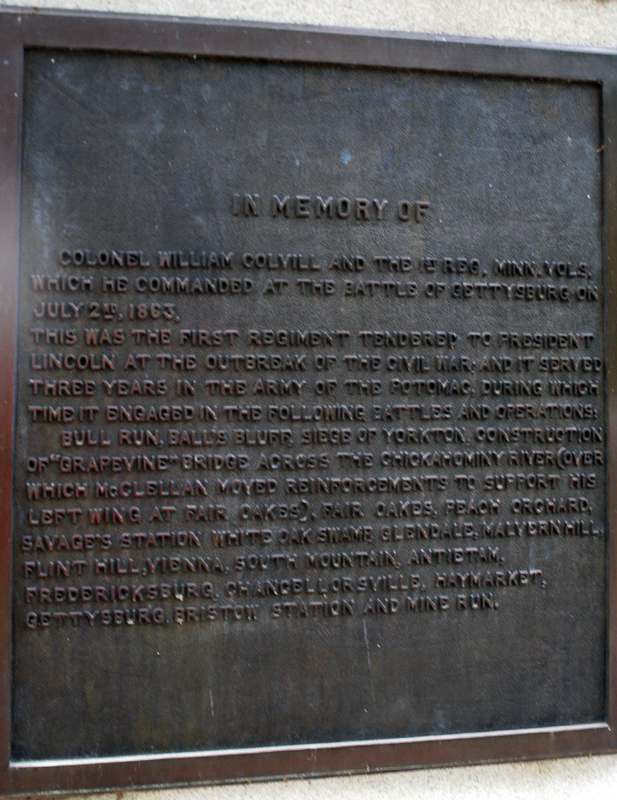

When the call went out on April 19, 1861 for the men of Goodhue County to form a volunteer infantry unit in service of the government, William Colvill was the first to sign his name on the sheet. He narrowly beat out his friend A. Edward Welch, who fell as they both raced to the sign-up sheet at front of the meeting hall. Colvill, at the age of 31, was one of the oldest men to volunteer. His age, good standing in the community, and his substantial 6’5” frame made him a natural pick for leader of the volunteers. Even though he didn’t have any previous military experience, he was elected Captain of the 100 men from the county just before they set off for Fort Snelling. This group of men became Company F of the First Minnesota regiment — the first regiment given to the federal army when the war began.

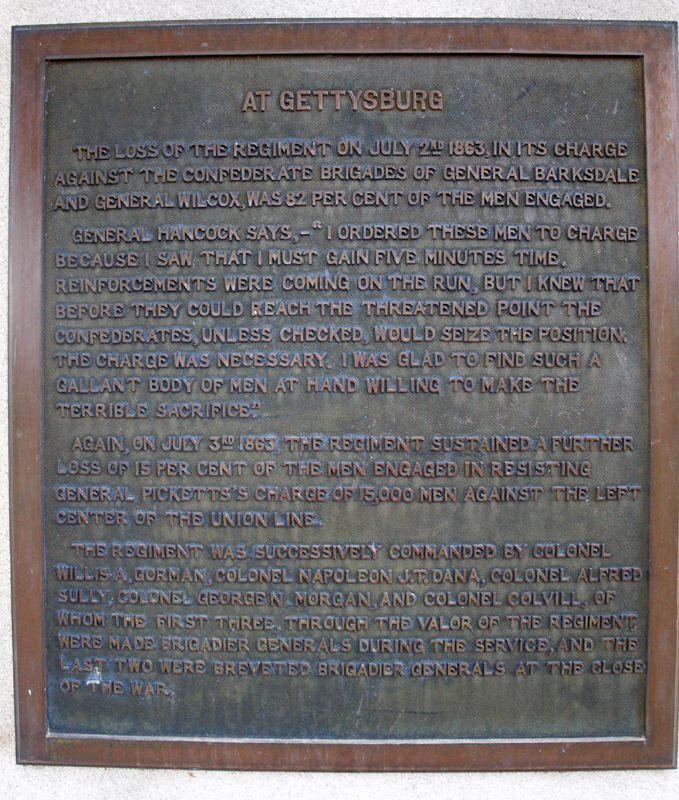

The regiment’s first action came at Bull Run. They went on to make significant contributions in the Battle of Balls Bluff, the Peninsula Campaign, the Seven Days Battles near Richmond, Virginia, and at Antietam in Maryland. However, it was the Battle of Gettysburg that proved to be Colvill and the First Minnesota’s most noteworthy action. By Gettysburg, Colvill had risen in rank; he became Major, then Lieutenant Colonel, second in command of the regiment by the end of 1862. When Colonel Morgan retired because of poor health in May 1863, Colvill was promoted to Colonel and put in charge of the First Minnesota.

In the early morning of July 2, the First Minnesota was marching toward Cemetery Ridge in Gettysburg. Colonel Colvill was still under house-arrest for the dishonorable actions of some of his men on June 29th. Upon hearing there would be a battle that day, Colvill was eager to lead his men in the fight. He asked General Horrow to relieve him of his arrest and the General agreed — he knew the First Minnesota would need Colvill’s steadfast leadership in this battle. The heroism of the First Minnesota on Cemetery Ridge is legendary. In order to stall a Rebel advance, the First Minnesota charged down the hill and met the Confederates head-on. With enemy shots coming from three sides, Colvill was hit at the top of his right arm with a minié ball that struck his backbone before lodging in the flesh of his shoulder blade. Colvill went on fighting until he was knocked off of his feet by another shot, this time shattering his right ankle. He managed to roll himself into a dry creek bed before falling unconscious. He wasn’t found until later that night when a soldier stumbled upon Colvill’s body while looking for his brother. The soldier ran back to camp and brought back several men to carry their leader up the hill and to a field hospital at a nearby barn.

After several hours, Colvill was readied for amputation but he rejected the surgery. With nothing more to be done for him that night, the doctors placed him under a large tree with several other Union soldiers. The tree provided little protection from the torrential rain that lasted all night, but Colvill never complained, instead offering words of encouragement to the other soldiers. The next day the doctors came back to see who could still be saved. Colvill was taken to Wolf Run where his foot was placed in the cool creek and a canopy was placed over his body to shield him from the sun. He was left there for several days with a flask of brandy before being moved to a private home in Gettysburg where his sister cared for him. Desperately wanting to return to Red Wing, he tried traveling home but only made it as far as Harrisburg before having to disembark the train and admit himself to a hospital. By October he was able to travel to Forestville to recover. Despite his wounds, he went back to the war in 1865, commanding the First Minnesota Heavy Artillery until the end of the war.

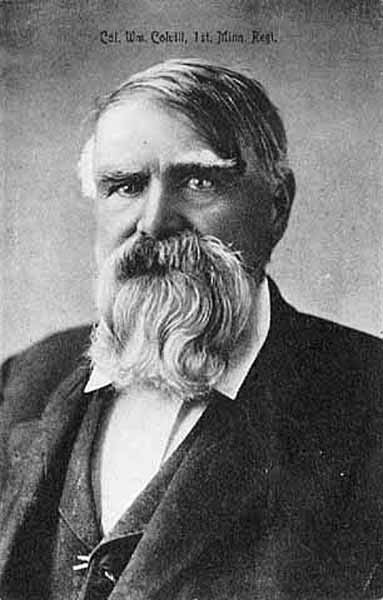

Colvill returned to Red Wing after the war, married fellow New York native Jane E. Morgan, and continued to practice law. He was elected to the Minnesota House of Representatives in 1865 and became the State Attorney General in 1866. He and Jane moved to Duluth in 1887 after President Grover Cleveland appointed Colvill to be the federal registrar there. After Jane died in 1895, Colvill moved to a piece of land on the north shore of Lake Superior near Grand Marais, The area became known as Colville (an incorrect spelling of his surname). He homesteaded here for several years before his failing health brought him back to Red Wing.

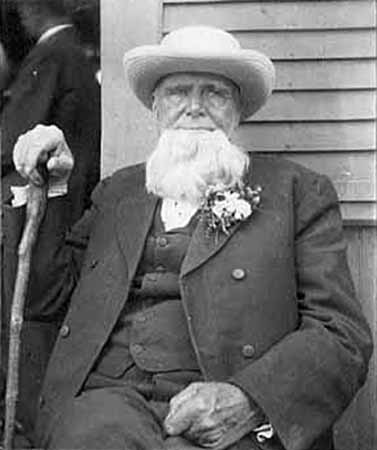

In the years after Jane’s death, Colvill faced several financial struggles. Friends in need could always count on help from Colvill in any manner which he could be of assistance, but strangers also benefitted from his generous heart. He seldom had any money because he would take legal cases for little or no pay. What money he did make was often given away to help people who needed it more than he did. As he got older, he relied on a $50-per-month pension, but most of that also went to help others. Even though he had a surly, disheveled appearance, the local children loved Colonel Bill — they would follow behind him as he walked home from work, shuffling with his cane on his shattered ankle, cheerily talking and laughing with him. He was often seen giving rides to local children in his carriage or horse-drawn sleigh.

Colvill’s illnesses became more frequent and made his last years difficult. Despite his health problems, he traveled to the Twin Cities in June 1905 to take part in a ceremony to transfer the Civil War flags to the new capitol building. He was always eager to spend time with his old regiment and talk with the men. Sadly, on June 13 — just one day before the ceremony — Colvill died in his sleep. His body laid in state at the new capitol, just outside the Governor’s reception room. His coffin was draped with a huge flag and an honor guard kept vigil as thousands of people paid their last respects. His body was then transported to Cannon Falls where he was laid to rest next to Jane.

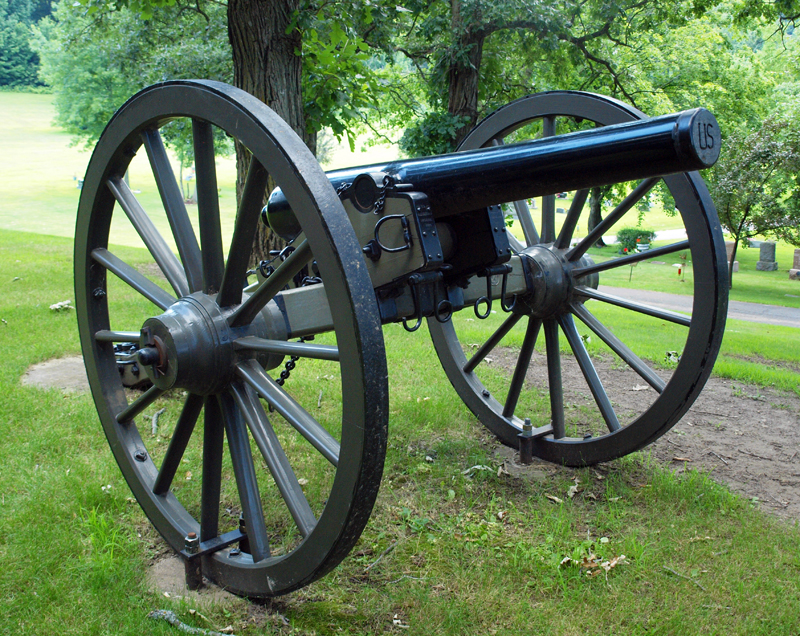

The bronze statue near Colvill’s grave was placed there in 1909. It was designed by Mrs. George Backus of St. Paul and mounted on a pedestal of Bedford stone. The monument was expanded further to include a balustrade and steps to the memorial, a Civil War cannon, and plaques commemorating the Colonel and the First Minnesota. The dedication of the improved monument was attended by President Calvin Coolidge (his address at the dedication can be read here), Minnesota Governor Christianson, and hundreds of regular Minnesotans that were eager to pay tribute.