Wilder Public Baths

It’s hard to imagine a time when taking a bath or shower in your own home wasn’t possible, but the convenience of showering on a regular basis is a modern luxury. One hundred years ago, many working-class homes in St. Paul lacked bathing facilities. People living in rooming houses and along the Mississippi flats didn’t even have running water. Public beaches were a popular way to wash away the dirt and sweat from hard work, but they were only available in the summer. Recognizing the public need for a year-round facility for people to clean themselves, the Amherst H. Wilder Charities established a facility where anyone could have a “shower bath”—no matter the weather.

Cornelia Day Wilder was the only child of Amherst and Fanny Wilder. She grew up on St. Paul’s swish Summit Avenue, just two houses down from the James J. Hill house. As a child, Cornelia recognized her privileged position in St. Paul and decided to use it to help the poor. Throughout her life, she volunteered her time and money to help the less fortunate. Through her stories from the front lines of helping the poor, Amherst and Fanny recognized the need to provide funds to benefit people in need.

Anxiety about a trip across the Atlantic Ocean with his wife in the 1880s caused Amherst Wilder to draw up a will. In it, he stated that he wished for his extensive estate to be split three ways: one-third to Fanny, one-third to Cornelia, and one-third to the future children of Cornelia and her husband. He specified that if Cornelia didn’t have any children, that portion of the estate should go toward the endowment of a charity “to aid and assist the poor, sick, aged, or otherwise needy people of St. Paul.” Fanny’s will also stated the same wish for the establishment of a charity with money from her estate.

Amherst Wilder died in 1898. Fanny and Cornelia began planning to make his wish to set up a charity with money from his estate a reality. However, it wasn’t until Fanny and Cornelia’s deaths, both in 1903, that the plan could move forward. Between 1903 and 1910 all three of the Wilder estates were involved in litigation as a result of potential heirs who sought to set aside the family’s wills—the wills were challenged in five different lawsuits during this eight year period. In the end, the wills were upheld as written. Since Cornelia and her husband never had children, and Fanny and Cornelia had both passed away, a significant amount of the Wilder estate went towards establishing the Amherst H. Wilder Charity.

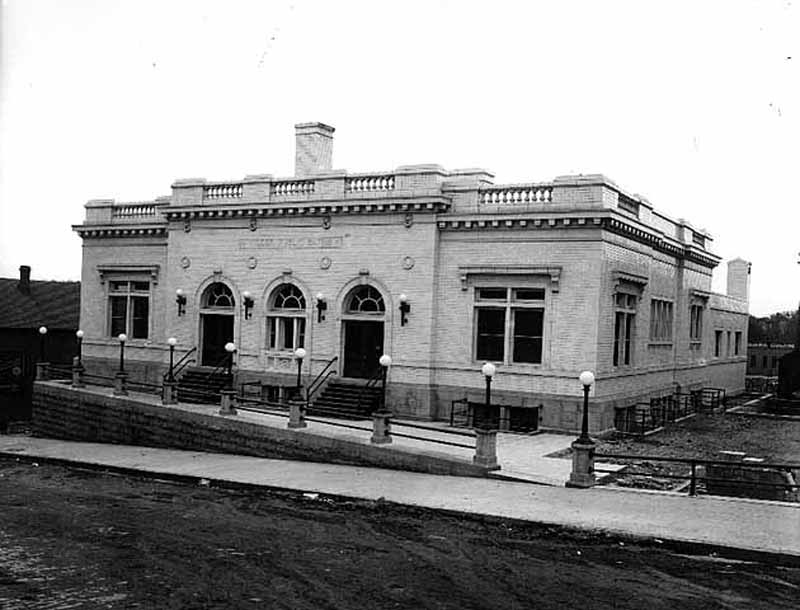

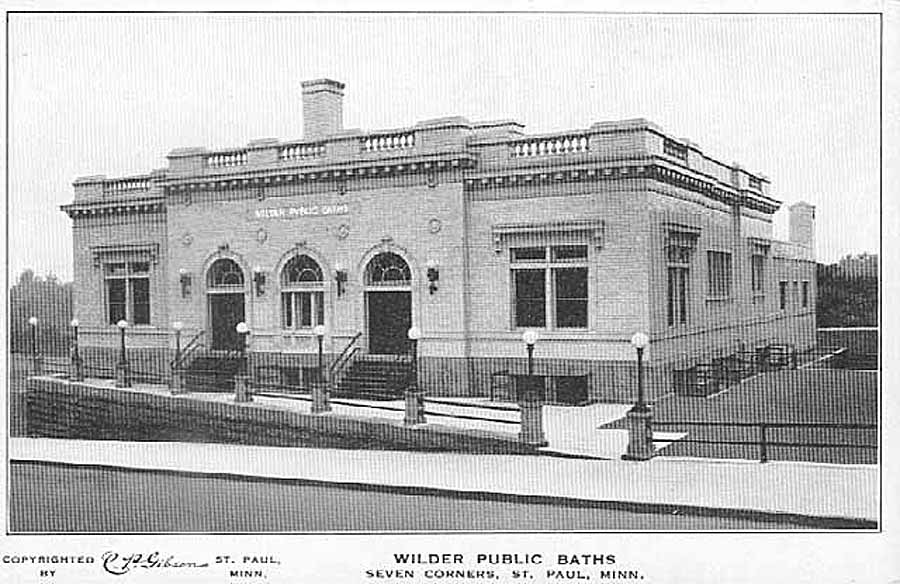

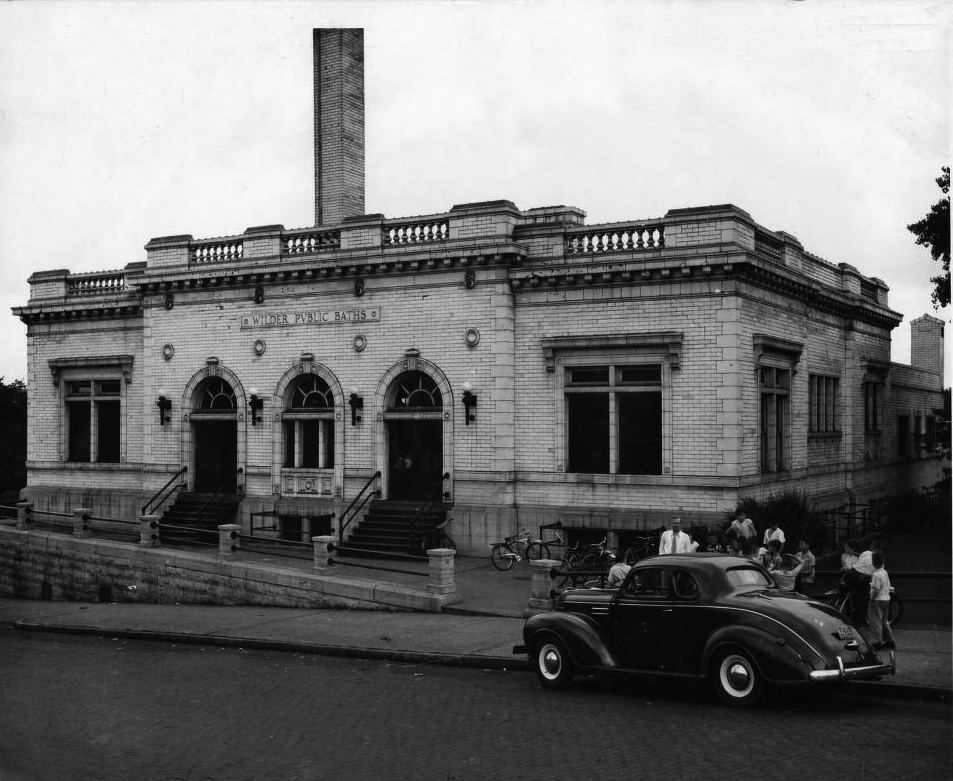

On May 25, 1914, the Amherst H. Wilder Charity opened the first public bathing house in St. Paul. In her will, Fanny Wilder specifically asked that money from her estate to be used to provide the residents of St. Paul with a place where anyone could come to swim or bathe. Built in the Seven Corners neighborhood, the modest but handsome white brick building featured 85 private shower stalls and a 30-by-70-foot swimming pool—the second largest in the upper Midwest. The charity negotiated with the City of St. Paul to provide the water needed at no charge, and the facility generated its own electricity, which kept the cost of operation low. In turn, the charity was able to provide shower baths, a clean towel, and a cake of soap for just two pennies. For just three more pennies, anyone could enjoy a shower and then rent a shapeless, blue tank suit and spend the day swimming in the indoor pool.

The response to the new bathing house was overwhelming and unexpected, which caused a few growing pains for the charity. The locker rooms were overcrowded, there were long waits for the showers during peak hours, only 24 lockers were provided for women, and African Americans were not permitted to use the facility. Another problem the charity faced was educating patrons about how to use the showers. Most people had never used a shower bath before, so instructions were posted to illustrate how to clean themselves with the overhead spray. “The first part of the shower bath is to wet the body all over with hot water, then come from under the shower and soap the body thoroughly until covered with a soapy lather; go back under the shower and rinse the soap off, after which the water should be regulated down gradually.”

The growing pains didn’t keep people away from the bathing house. Each year it admitted more bathers than the previous year. In the first four years alone, nearly one million people used the facility to shower or swim. Many patrons used the facility twice per week. Between July 1, 1917 and June 30, 1918, the charity reported 238,687 total users—196,123 used the showers and 42,564 used the pool. July and August were the busiest months for the facility and men used the showers twice as much as women. During the dust storms that blanked St. Paul in 1934, over 2,100 people used the showers in one day.

By the 1940s, more of the City’s poor had their own bathrooms and the showers were replaced by the pool as the top-drawing attraction at the bathing house. The facility quickly began to lose money. The Charity sought another organization to take over operation of the showers and pool, to no avail. The Wilder Charities closed the bathing house, remodeled it, and reopened as the Amherst H. Wilder Health Center in the 1950s. In 1974 the Health Center closed for good and the Wilder Foundation sold the building to the United Way. The final chapter for the Wilder Public Baths building was written in 1992 when its final owner, the Seven Corners Hardware Store, demolished it to make way for a parking lot.

Today, the Amherst H. Wilder Foundation continues to serve low-income children and older adults in the St. Paul area.