Lilac Way: Showcase of the Belt Line

Although it’s difficult to tell now, Highway 100 in the west metro was once one of the most beautiful and serene roads in the nation. The roadway was conceived just after the start of the Great Depression as a joint venture between the National Recovery Work Relief Program (which would later become the Works Progress Administration) and the Minnesota Highway Department. Highway 100 would be the first piece of a larger road system that would bypass the Twin Cities, called the Belt Line. This western portion of the project would be the showcase section because of its innovative design and thoughtful landscaping.

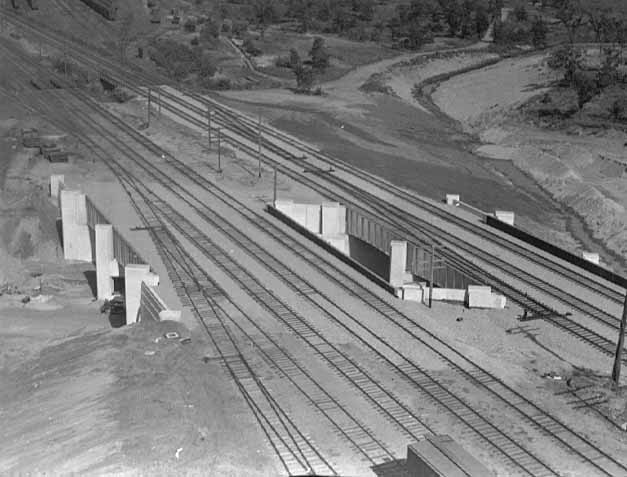

The Minneapolis and St. Paul Belt Line was the brainchild of Highway Department Engineer Carl Graeser. He envisioned a safe, efficient roadway that would circle Minneapolis and St. Paul in a 66-mile loop, while providing drivers with an aesthetically pleasing experience. The Belt Line would feature two paved lanes for traffic in each direction, have a wide center median and 350-feet of right-of-way on each side of the road. Access to the Belt Line from driveways and side-streets would be limited, and bridges would be built for railroad tracks and road crossings. Graeser’s vision began to move forward in 1933 when two survey crews began recording data for a twelve mile, north-south route in a rural area west of downtown Minneapolis. Construction on the Belt Line began in 1934 at 50th Street/Vernon Avenue in Edina.

With a crew of thousands of men working through the National Recovery Work Relief Program, Carl Graeser saw the first phase of construction completed by the end of the 1934 season. The first section of the Belt Line stretched north from 50th Street/Vernon Avenue to Excelsior Boulevard. Phase two took the roadway further north to Wayzata Boulevard in 1935. The final section between Wayzata Boulevard and Highway 52 (now 81) in Robbinsdale would take two years to complete. This section of road required more bridges for railroad traffic and three cloverleaf interchanges—the first in the northwestern United States. In addition to the additional work, National Recovery Work Relief Program workers were replaced with Works Progress Administration workers which slowed construction for a period. Landscaping along the new road was also taking place during this last phase of construction which employed several hundred additional men. During this phase of the project, Carl Graeser oversaw the work of more than 4,000 men. It has been reported that no one in the Minnesota Highway Department before or since Graeser has ever managed so many employees at one time. The majority of construction on this section of the Belt Line was completed in 1938.

The Minnesota Highway Department chose landscape architect Arthur Nichols to design a concept for this scenic section of the Belt Line. Nichols had plenty of experience working on large-scale landscape projects such as the site plan for the Minnesota State Capitol approach, the University of Minnesota, and the Congdon Estate in Duluth. Nichols presented plans for natural landscaping with native plants and plenty of wide open space for fresh air to flow. Native grasses would be allowed to grow in the 30-foot medians and along most of the right-of-way. Various types of deciduous trees, shrubs, and vines were to be planted along the right-of-way to enhance the natural terrain. The Roadside Development Unit of the Highway Department prohibited planting flowers or flowering shrubs along any roadway, but an exception was made for this showcase section of road. The Minneapolis Journal suggested planting lilac bushes along this section of the Belt Line, likening it to the cherry blossoms in Washington D.C. An exception was made by the Roadside Development Unit, and the plan was approved. Several hundred WPA workers set about planting twelve varieties of lilac bushes. In the end, more than 30,000 deciduous trees and over 7,000 lilac bushes were planted giving the new road its nickname, Lilac Way.

In addition to landscaping along the road, Nichols also developed five roadside parks for travelers. Each park would be several acres in size and have picnic areas, a triple fireplace for cooking, and unique features such as rock gardens or waterfalls. Lilac Way was a destination for lazy Sunday drives, and the roadside parks became gathering places for all walks of life. Families would motor in from the countryside or out of the city to picnic along Lilac Way. When the lilacs were in bloom, it wasn’t uncommon to pull into one of the roadside parks only to find it full of children playing and exploring while their parents cooked a meal in one of the triple fireplaces, known as beehives, and socializing until sunset.

Excelsior Boulevard Park was the southernmost roadside park along the route. It was located at the northwest corner of Excelsior Boulevard and Highway 100. The entire park and all of its fixtures were lost to construction when Highway 100 was improved in the area.

Just a few miles north, St. Louis Park Roadside Park was located at the southeastern corner of Highway 7 and Highway 100. A portion of this park remains near the NordicWare tower. The remaining portion of the park has been renovated and renamed Lilac Park. It features several restored stone picnic tables, a council ring, and one of the original beehive fireplaces. This beehive, along with another located in Graeser Park, are the only two remaining beehive fireplaces in the nation.

The original Lilac Park was located northeast of the Highway 100 intersection with Minnetonka Boulevard. The park was lost to construction, but the beehive fireplace and picnic tables were saved and moved to St. Louis Park Roadside Park (which is now called Lilac Park).

Both of the Roadside Parks in Golden Valley have been lost. Glenwood Park was located at the northwestern corner of Highway 100 and Glenwood Avenue, and Blazer Park could be found between Lilac Drive and Highway 55 near Highway 100. Glenwood Park was the first to be demolished. Blazer Park hung on into the early 2000s, but resident complaints about its run-down appearance and lack of improvement funding from the city sealed its fate. Blazer Park and its remaining stone structures were not saved when construction began on this section of Highway 100 in 2001.

Dedicated in 1939, Rock Garden Roadside Park in Robbinsdale is the largest and most intact example of the parks that peppered Lilac Way. The park has been renamed Graeser Park in honor of the Father of the Belt Line, Carl Graeser. Although the park has been dissected by Highway 81, several remaining pieces of the original park remain. The original beehive fireplace and curved overlook wall can be seen from the parking area. The stone picnic tables that once filled the area were removed when the park was used for the storage of construction equipment, but the footings can still be seen. Behind the beehive, twelve stone steps lead down to the original rock garden. Visitors can follow a flagstone path that winds past four stone niche benches and two artificial ponds that once held about three-feet of water. One pond had a waterfall feature; the other had a conical-shaped stone fountain in the center. The park land that now sits across Highway 81 was included in Rock Garden Roadside Park in 1940. This part of the park once boasted several picnic tables, a large limestone council ring, a well and pump for fresh water, and the original stone and lumber “roadside parking” sign.

The five roadside parks were all constructed between 1938 and 1939. Arthur Nichols and his army of WPA artesian stonemasons followed the National Park Service’s rustic style for all five parks. Only local materials were used—all of the limestone used came from along the Minnesota River near the Mendota Bridge— and the structures were all built by hand using only a hammer and chisel. By 1940, this western leg of the Belt Line and all of the parks were open for travelers. It would take another ten years for the entire Belt Line to circle the Twin Cities.

Only one of the original cloverleaf interchanges remains where Highway 100 intersects with Highway 12/394. Most of the right-of-way along the highway has been filled with glass office buildings and car dealerships. The road that was once so far away from Minneapolis that residents didn’t think anyone would ever use it is now a major north-south commuter artery through first-tier suburbs. Soon, most of the Graeser-designed, WPA-built bridges will be demolished to widen Highway 100 in order to accommodate the growing number of commuters who use the road each year.

Click here to see several historic photos of the last parks along Lilac Way.