James J. Hill’s North Oaks Farm

James J. Hill was the preeminent transportation pioneer in the American Northwest. He arrived in St. Paul, Minnesota on a steamboat in 1856 and planned on becoming a trapper and trader. Instead, he found work with a steamboat company. During the Civil War, Hill learned the business of buying, selling, and transporting goods. Through connections made during this time, he was able to move into a more lucrative position with the St. Paul & Pacific Railroad. His entrepreneurial spirit led him to start a new business which would supply the StP&P with coal for fuel. Skip ahead to 1883 and Hill had acquired the StP&P and incorporated it into the St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Manitoba Railway Co. and was now the railway president. Under Hill’s direction, the railway prospered and its net worth increased by $24 million in just five years.

As James J. Hill’s professional interests took his railway west to the Pacific, his personal interests were firmly locked in Minnesota. He dreamed of experimenting with cutting-edge agricultural practices that would improve farming for the immigrants that were flooding into Minnesota on his railroad. In 1880, he acquired 160-acres of land on Lake Minnetonka’s Crystal Bay. He named it Hillier Farm. Hill set his mind to use the farm to breed stock that would improve the cattle available to farmers along his railroad lines. In December of 1881 Hill began purchasing land in the fertile Red River Valley near Hallock, Minnesota. The 45,000-acres of land he purchased became known as Humboldt Farm and was run as a basic bonanza farm. Eventually, 3,000-acres of Humboldt would be split off and managed by Hill’s youngest son, Walter, under the name Northcote Farm. Finally, in 1883 Hill purchased 3,500-acres of land in Ramsey County for $50,000. This investment would expand to nearly 5,500-acres and serve not only as a farm, but also as Hill’s country estate. It became known as North Oaks Farm.

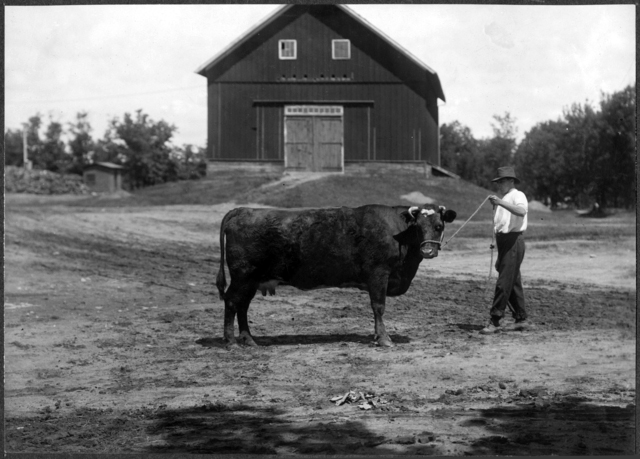

For the first ten years, the North Oaks Farm operated as a stock farm and base for Hill’s efforts to breed a dual-purpose cow. The concept of breeding beef cows that would also produce milk was very popular during this time. Experts in husbandry at the University of Minnesota were also working to produce this type of cow. Although Hill invested an enormous amount of money to breed a hybrid beef/dairy cow, his dairy results were marginal, while the beef was considered excellent. It seemed impossible at the time to have a cow that could be exceptional at both. However, the experience Hill and his workers received during this endeavor went on to help them in other ways. The North Oaks Farm gained a reputation for breeding exceptional beef cattle. Each year his Aberdeen Angus and Shorthorn cows from North Oaks would travel by train to Chicago to take part in the Fat Stock Show. The cattle won several prizes at the show over the years. In 1889 alone his Aberdeen Angus brought home $700 in prizes from Chicago.

Hill had set his sights on experimenting with more diversified farming by the 1890s. His famous Aberdeen Angus herd was sold off in 1893. Between 1893 and 1895 North Oaks only housed a handful of cattle, along with some purebred pigs and a successful corn operation. In 1896, Hill began acquiring the elements needed to become extensively diversified. A reporter from the St. Paul Pioneer Press visited the farm that summer and reported seeing various breeds of horses that were being raised as carriage horses, dairy cows, sheep grazing in the pasture, fat Berkshire pigs enjoying the shade of an oak grove, plenty of elk and deer, and even a herd of buffalo that roamed through the range. Hill also raised poultry—Mammoth Bronze turkeys and Black Cochin or Plymouth Rock chickens.

The North Oaks Farm also experimented with finding the best feed and fertilizer. Hill determined that root vegetables such as turnips, beets, and cabbage, combined with hay and oilcake, provided the most nutritious winter feed for the animals, and provided an increased market weight that added an average profit of $2 per head. By 1912, the superintendent of the farm switched to feeding dairy cattle a diet of oats, barley, and cowpeas over the winter. Feed was necessary for the animals, but the right fertilizer was essential for crops. A very specific mixture of nitrate of soda and acid phosphate was used beginning in 1914 with excellent results. Hill hired men to present the findings and recipe to farmers all along his rail line.

Hill’s most successful venture was his Ayrshire dairy cows. He received two awards from the international Ayrshire Breeders Association—one for home dairy milk and the other for butter production. The process to even be considered for these awards was lengthy and tedious. The farm was required to keep daily records for an entire year detailing the weight of milk, calving, food, and care of the herd. Each month the records and a sample were sent to the state experiment station to verify the findings and calculate the butterfat content.

North Oaks was Hill’s favorite farm. Even though it was the least profitable of the three, it suited all of his interests and was close to his home in St. Paul. In reality, Humboldt was the only farm that reaped significant profits. If North Oaks or Hillier produced a profit, it was invested right back into the operation. The cost to maintain the North Oaks Farm, and pay the 40 men that worked there, only cost Hill $28,000 in 1914, no doubt adding to why Hill favored this farm above the others. North Oaks also provided the Hill home in St. Paul with vegetables, fruit, milk, butter, eggs, and fresh flowers. A cart would make the trip from North Oaks to St. Paul each morning with the freshly harvested goods.

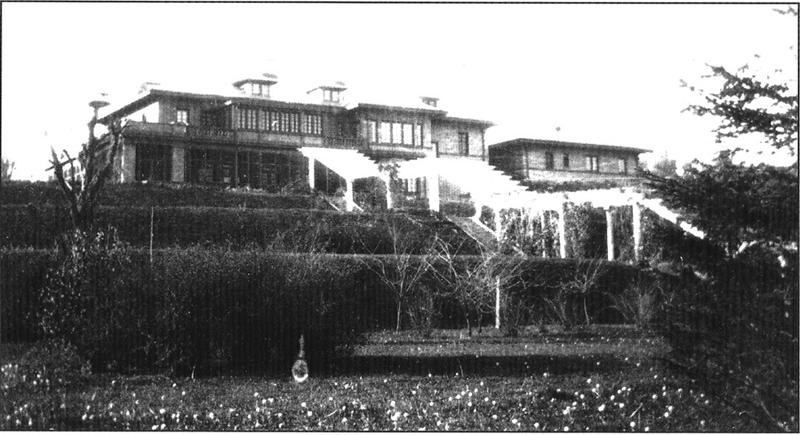

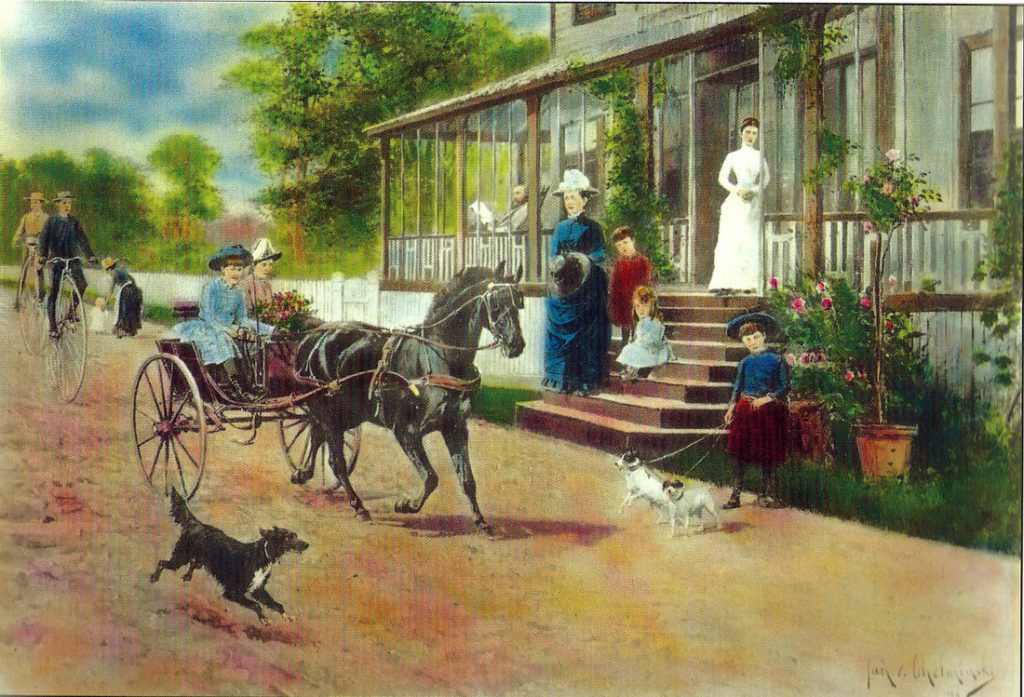

The Hill family preferred to spend most of the summer at the farm in an estate that overlooked Pleasant Lake. The family would always entertain guests at the farm in the weeks surrounding Independence Day. Favorite activities included fishing and swimming at Pleasant Lake, riding horses, shooting, and going for country drives. Hill was eager to show his farm off to visitors and guests and could spend hours giving tours of the facilities and fields. James J. Hill managed all of the landscaping at North Oaks and spared no expense—he spent $2,500 alone in 1914 to decorate around a new brick house near the lakeshore that had been completed that year. His wife, Mary Hill was in charge of deciding which vegetables and flowers would be grown each year since she oversaw the staff of cooks and servants that would use them at their mansion in St. Paul.

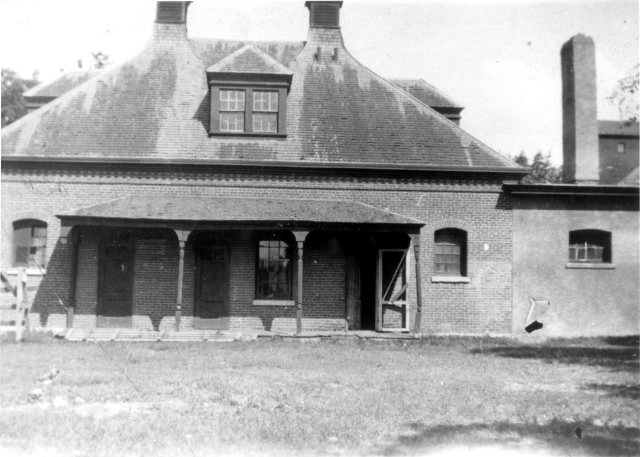

After Hill’s death in 1916, the operation of the North Oaks Farm fell to his son, Louis Hill Sr., who shared his father’s passion for farming. It wasn’t until the 1950s that Louis Hill Jr. divided the farmland into smaller parcels for a carefully-planned residential development. The grand estate on the lakeshore was demolished, along with the greenhouses and barns. Even the graves of James and Mary Hill were moved to Resurrection Cemetery in St. Paul. Only three of the original forty buildings remain; the creamery, granary, and blacksmith shop/engine house.