John S. Bradstreet: The Apostle of Good Taste

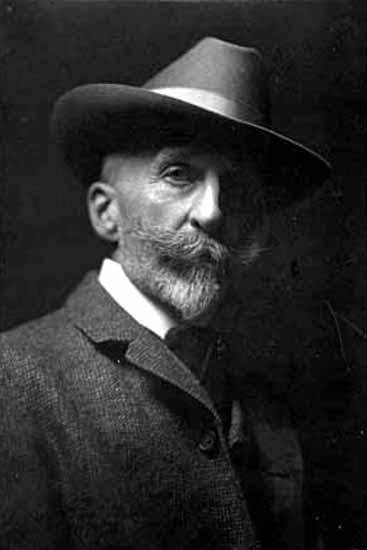

Names like Louis Comfort Tiffany and Gustav Stickley are well rooted in many American’s minds as two of the key players in interior design and the decorative arts of the early twentieth century. For the emerging upper-middle class in Minneapolis, it was a craftsman closer to home that excelled in creating handsomely-crafted pieces locally. John Bradstreet’s position as a tastemaker in the city was solidified into history when the Minneapolis Journal eulogized him in 1914 by proclaiming, “If this section of the country is to furnish a name that will be known to the America of one hundred years from today, that name is more likely to be that of John Scott Bradstreet than any other.”

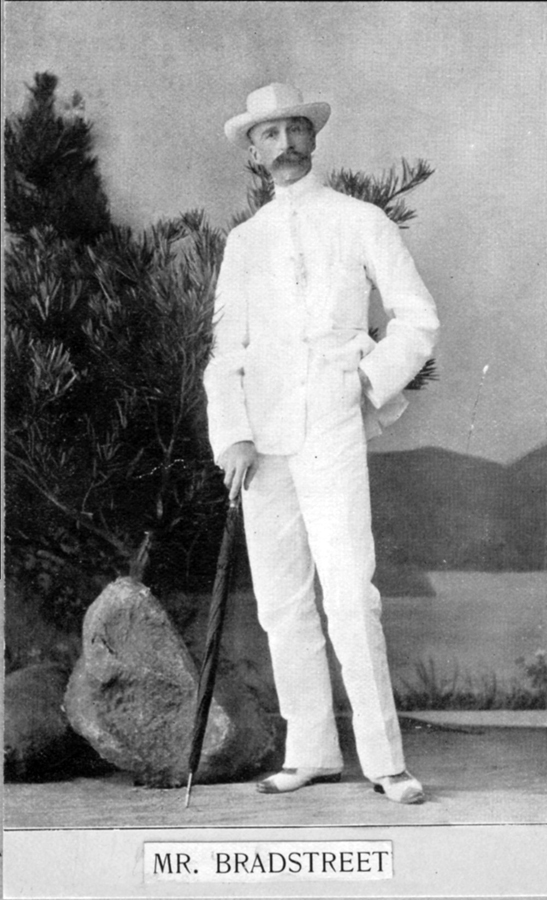

Bradstreet got his start in Minneapolis in 1878 when he established a custom furniture business partnership with Edmund Phelps. The firm grew steadily over the next five years, and their showroom eventually occupied six floors of the Syndicate Block on Nicollet Avenue in Minneapolis. Bradstreet wasn’t only building his business; he was earning a reputation for being the city’s leading interior decorator and furniture designer. In 1884, Phelps sold his share of the business to pursue other ventures. That same year, Bradstreet partnered with the Thurbers of Gorham Manufacturing and formed Bradstreet, Thurber, and Co.

Bradstreet used his blooming influence to steer the taste and style of Minneapolis. During one of his first commissions, Bradstreet introduced the Moorish style to the city by designing the interior of Phelps’ home on Park Avenue. He went on to redecorate the interior of the Grand Opera House in Minneapolis in the style in 1897. From there, Bradstreet became an enthusiast of the Japanese style. Although he moved through popular trends in design because of his client’s tastes, he never mastered a single aesthetic better than his hybrid Japanese/Moorish/Arts and Crafts style. Those mixed-style design elements created Bradstreet’s unique, signature style that was highly sought after, and praised by design giants like Tiffany and Stickley.

The Bradstreet, Thurber, and Co. building and all of its inventory were heavily damaged by fire in 1893. Around the same time, Bradstreet and the Thurbers dissolved their company and went their separate ways. Bradstreet decided to operate his business under his own label. Together with Frank Waterman and Fannie Jaquess, he incorporated under the name John S. Bradstreet and Company. Two years later, Bradstreet secured a ten-year lease at a residence at 327 South Seventh Street in Minneapolis with the intent of opening his studio, showroom, and warehouse inside the stately home. First, he would need to remodel the building to suit his vision.

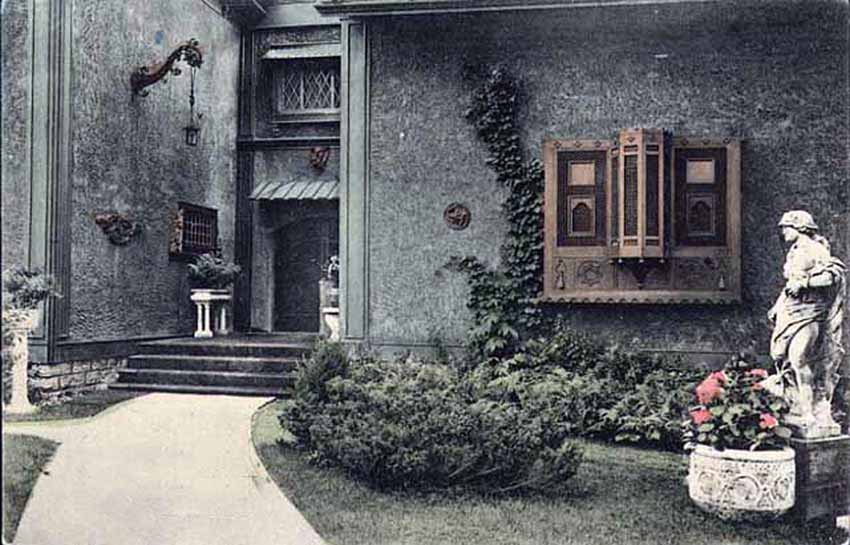

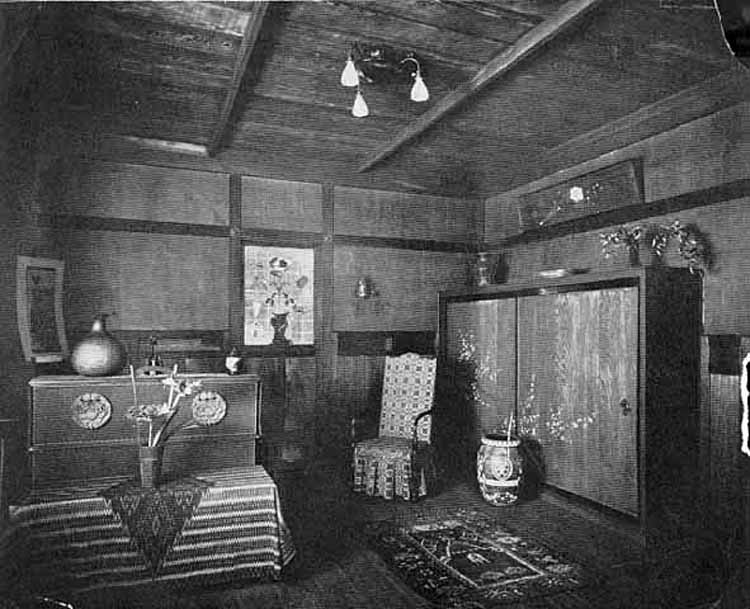

Bradstreet spent the next several months transforming the Italianate-style villa into an Oriental retreat. He redesigned the facade of the house, constructed a large, attached shop and showroom, and installed electricity. Intense interest from his new neighbors and excited patrons made for an enthusiastic grand opening of the John S. Bradstreet and Company Crafthouse in January of 1904. By 1912, Bradstreet’s growing popularity allowed him to acquire adjacent lots and steadily expand the property to include a complex of showrooms, offices, and warehouses. Several new workshops were also added to the property. Separate facilities for cabinetry, painting, gilding, upholstery, ceramics, and custom lighting fixtures were built to accommodate the number of artists working for the company. His workshops employed more than eighty craftsmen, including several from Japan and Scandinavia that Bradstreet handpicked because of their talent. Perhaps the most notable technique developed in Bradstreet’s workshops was to modernize the process of one of his favorite design elements, jin-di-sugi.

Jin-di-sugi utilized ancient cypress trees that had been repeatedly submerged in water over hundreds of years. The structure of the wood grain resulted in organically shaped, raised lines in the wood. Craftsmen would then use the unique shape of the wood as the basis for carving. Bradstreet experimented extensively with this technique in the Crafthouse workshop. He hoped to develop a method to replicate the weathering without having to procure ancient cypress trees. He discovered a combination of burning or charring the wood and removing the softer fibers with brushes yielded the desired contours, and a left a velvety, lustrous finish. This achievement earned Bradstreet considerable acclaim. Louis Comfort Tiffany declared Bradstreet’s technique to be the most unique and artistic treatment of wood he had ever seen.

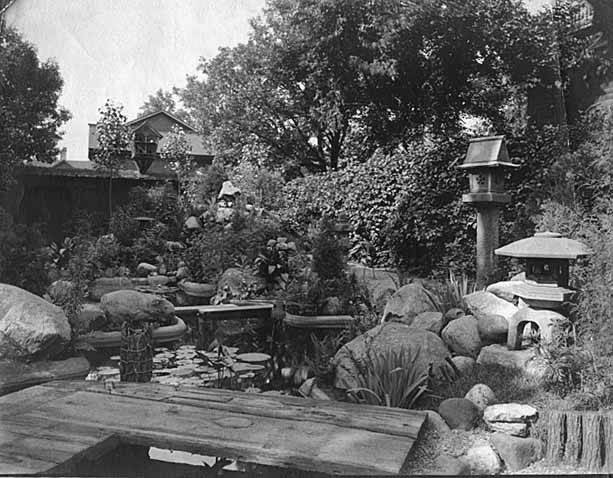

Bradstreet’s Crafthouse became an immediate sensation in the city and drew commissions from throughout the upper Midwest. The Crafthouse was separated from the street by a large Japanese garden. To reach the entrance, clients passed under an archway—known as a torii—and then followed a curved walkway to the main entrance. Inside, the entry hall was paneled in jin-di-sugi and filled with elegant furnishings. Bradstreet displayed items manufactured by his craftsmen in an expansive fifty-six-foot-long gallery that featured hammer-beamed ceilings, skylights, and cloth-covered walls. The adjacent hall’s main fireplace was flanked by two plaster elephant heads that Bradstreet had salvaged from the Grand Opera House, which was razed in the 1890s.

In his Crafthouse, Bradstreet strove to provide an atmosphere of a museum for decorative arts. The design encouraged visitors to poke through the rooms to discover artifacts hidden away in quiet corners, much like how he discovered items on his travels. Outside, the Crafthouse’s Japanese gardens were lit by paper lanterns. A pond and rock garden were surrounded by shrubs, plants, and potted dwarf trees. A stream of water fell from the mouth of a bronze dragon that stood in the middle of the pond. A small bridge—made from discarded planks of wood used by the Japanese government during the St. Louis Exposition— served as a walkway over the pond. These items were unobtrusive in the garden but became a delightful focal point. Bradstreet often enjoyed informal meetings with his craftsmen in the garden because of its natural tranquility.

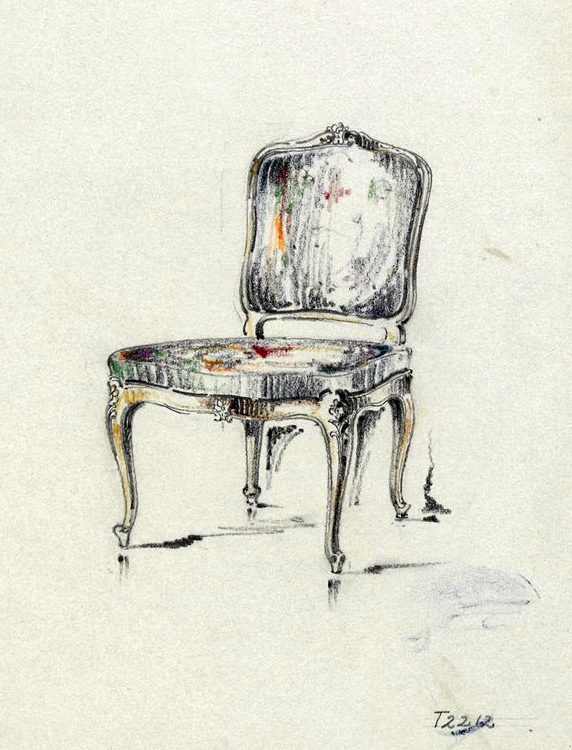

Throughout his career, Bradstreet endeavored to harmonize the existence of eastern and western design principles. Local support for his work allowed Bradstreet and his craftsmen to create decorative elements that were unique, rather than the products of a factory’s assembly line. He created a home for handicrafts, and his Crafthouse became the ultimate expression of himself and his tastes. Bradstreet’s business associate once explained to a client that although an ornately-carved Bradstreet lotus table could be purchased for $65.00, “The possession of this table will prove as satisfying as a grand painting by one of the Old Masters and similarly, besides being exclusive is as difficult to state its real worth in dollars and cents.” Bradstreet always stayed true to his eclectic style and gentle, sensitive nature and emerged alongside Tiffany and Stickley as a progressive and innovative artist, which cemented his place in decorative arts history.

Bradstreet’s Crafthouse was all but abandoned after his death in 1914. His business associates liquidated the inventory at the showroom. Craftsmen worked for several months to complete work on all of the outstanding orders before leaving their beloved workshops for good. The doors were then shuttered. In 1919, the entire complex was razed.

One of the finest examples of Bradstreet’s design style can be found at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The entire living room of the William and Mina Merrill Prindle home in Duluth was disassembled and moved to the museum in 1981. Known as the Duluth Room, the exhibit features some of Bradstreet’s most famous design elements— jin-di-sugi carvings, Tiffany glass, Japanese elements mixed with Arts and Crafts style, and one of Bradstreet’s most original and successful designs; the lotus table. In a nearby part of the museum, a fireplace that Bradstreet designed for the Joseph Sellwood residence in Duluth is also on display. However, if you’re looking for the largest, completely intact collections of Bradstreet’s work within a single residence, look no further than Glensheen. Bradstreet designed the Breakfast Room and most of the third floor for the Congdon family. It’s been said that Glensheen currently holds one of the most inclusive collections of his work in Minnesota.

Christie’s Auction House in New York acquired a small, Bradstreet-designed lotus table from a home in Massachusetts in 2008. At auction, the table sold for just under $500,000.00.

More photos: