St. Agatha’s Conservatory of Music and Art

As the nineteenth century began to wind down, the residents of Minneapolis and St. Paul became eager to establish institutions that would nurture American culture while enhancing a reputation of philanthropy within the music and art communities of the Twin Cities. The task of enriching residents with these types of cultural institutions was taken up by notable names like William Dunwoody and James J. Hill—both contributors and trustees of The Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, and T.B. Walker—founder of the Walker Art Gallery. From there, establishing schools of fine art and music education was made a priority. The first of these schools, St. Agatha’s Conservatory of Music and Art, was established in 1884. The Northwestern Conservatory of Minneapolis (1885), The Minneapolis School of Art (1886), and the St. Paul School of Fine Arts (1894) followed soon after.

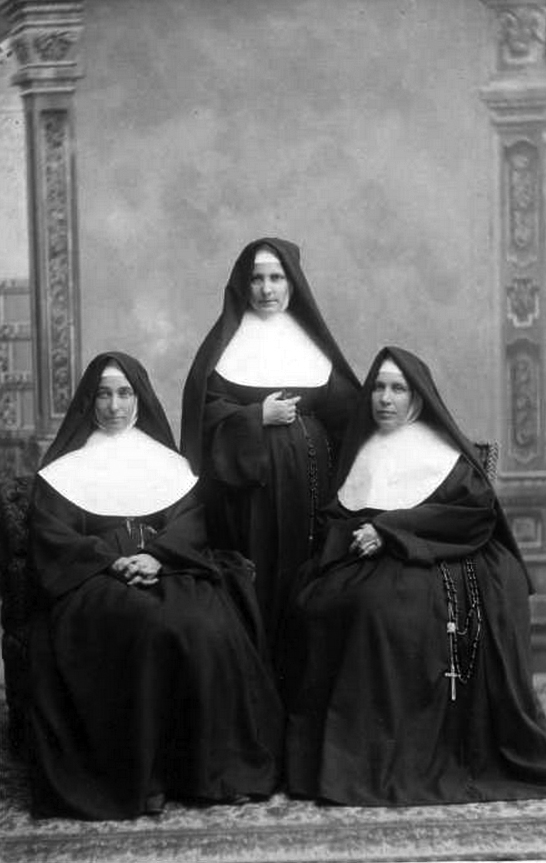

Originally established under the name St. Agatha’s Conservatory and Convent, the school was conceived by the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, St. Paul Province, under the guidance of Mother Seraphine (a.k.a. Ella Ireland—sister of Archbishop John Ireland).The initial school and convent were located in a rented home at Tenth and Main Street in St. Paul. It housed twenty sisters who taught in parochial schools around the city. The convent was intended to be entirely self-supporting. Classrooms were added so the sisters could teach music and needlework in the evenings in order to generate the funds needed to run the facility.

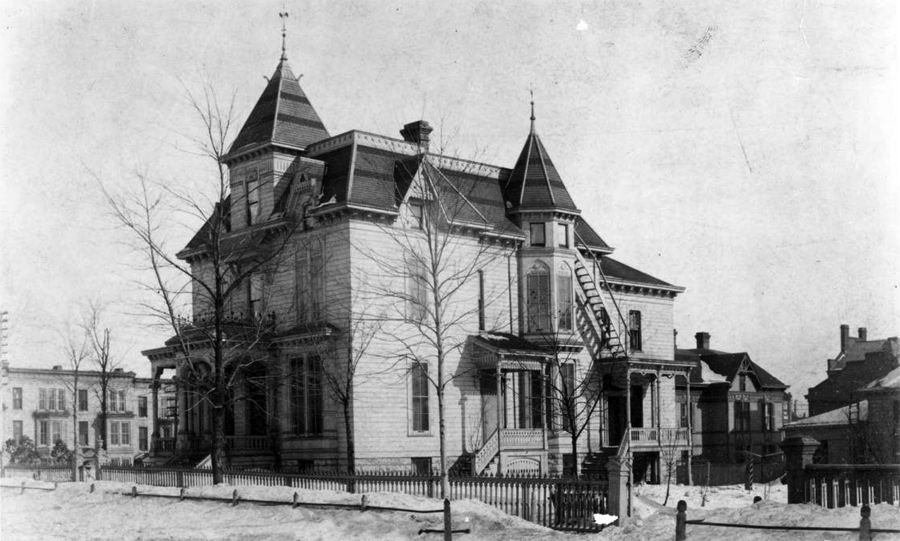

By 1886, the convent and conservatory had generated enough money to move into a larger building. The province purchased a wood frame house near Cedar and Exchange Streets. The name was changed to St. Agatha’s Conservatory of Music and Art, but the building still acted as a home for sisters teaching in downtown parochial schools. That same year, Mother Seraphine charged her cousin, Sister Celeste Howard, with running the school and convent. Enrollment in art, music, and kindergarten classes increased after the move. Students were drawn to the school from wealthy St. Paul families who lived nearby. This rapid growth lead to the construction of a two-story addition to the property in 1892, and additional renovations to turn a barn into classrooms in 1898. The property expanded even further in 1901 when the Vocal Music and Music Expression departments were added to the school. Several years later, the sisters embarked on their largest building project yet—a new, six-story building with a connected chapel.

The new building was constructed on the southwest corner of Exchange and Cedar. It was designed in the Beaux-Arts style and featured a rare exterior, curving double staircase that led visitors to the main entrance from Exchange Street. The brown brick exterior was ornamented by a pressed copper cornice between the fourth and fifth stories, and smaller cornices above the sixth story. At the rear of the building, a wing of similar style and ornamentation houses a convent chapel that was used by the sisters who lived on the top floors of the main building.

Administrative offices, two parlors, study rooms, a library, community room, and infirmary were located on the first floor of the school. Oak and maple woodwork, plaster moldings, and marble baseboards were present throughout the first level. Each parlor features a brick fireplace with porcelain tiles painted by the sisters, and glass chandeliers. The art classrooms were located on the second floor, along with the chapel at the rear of the building. The remaining floors were used by the sisters as a convent. A kitchen, dining room, community hall, and dormitory-style rooms were located on the upper floors and were self-contained from the school. The sixth floor featured a rare loggia with large rectangular openings and iron grillwork railings. Here, the sisters were able to relax in the privacy of their home while enjoying warm summer evenings high above the city.

By 1912, two years after the new building opened, the school had an enrollment of 817 students. At its peak, St. Agatha’s had an enrollment of 1,100 students in its art, music, dance, and drama classes. Class offerings included piano, violin, banjo, organ, mandolin, guitar, music history and theory, harmony, voice culture, counterpoint, elocution, languages, painting, drawing, china decorating, drama, and dance. St. Agatha’s offered students a competitive curriculum and several degree programs. Graduation from a program at St. Agatha’s often facilitated acceptance at schools such as Julliard and the Eastman School of Music.

Students weren’t the only ones encouraged to advance their learning in the arts. The sisters endeavored to become better instructors by traveling abroad to study art and music, or by earning degrees themselves. Several sisters at St. Agatha’s had music or art degrees from schools like Columbia University, the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music, Julliard, and Northwestern University. Independent, secular instructors were retained to ensure St. Agatha’s was providing the best arts education available—not just the best available from a school in the Midwest, or from a parochial school.

St. Agatha’s favored religious Renaissance art as a model for instruction. Three sisters from the school were sent to Munich and Florence by Mother Seraphine to sharpen their skills. Archbishop John Ireland supported furthering their education and sent letters of introduction with them to facilitate their travels. While abroad between 1908 and 1910, sisters Marie-Teresa, Anysia, and Sophia replicated more than 300 paintings to send back to St. Agatha’s. These replicas served as an important and early contribution to art education in St. Paul and Minneapolis. School groups from all over the Twin Cities converged on St. Agatha’s to study the paintings. The copies also served as a source of revenue for the school; the area’s wealthy residents often commissioned reproductions of famous Renaissance art from the sisters.

Revenue from St. Agatha’s rarely went back to the sisters. Instead, they chose to reinvest the income into the development of educational and health care facilities throughout the state. The Sisters of St. Joseph directed funds toward established institutions like St. Joseph’s Academy and St. Joseph’s Hospital in St. Paul. St. Mary’s Hospital in Minneapolis, the College of St. Catherine, and thirty-seven parochial schools across southern Minnesota also received partial funding from St. Agatha’s.

Enrollment at St. Agatha’s and nearby parochial schools started to decline as people moved further from downtown in the 1930s. By the 1940s, most schools offered their own art and music courses. After nearly eight decades as the premier school of art and music in the Twin Cities, St. Agatha’s Conservatory of Music and Art closed in 1962.

The influence St. Agatha’s Conservatory of Music and Art had on generations of young Minnesotans can still be seen in the Twin Cities. The sisters are credited with giving thousands of students the opportunity to receive a quality arts education that provided a base for a metropolitan area now recognized as a thriving arts center. The beautiful building that cost the Sisters of St. Joseph $150,000 to build still stands. Although the building now houses offices, much of the interior elegance remains on the first and second floors. Fittingly, the McNally Smith College of Music sits in the shadow of the former conservatory.