The Eight Days in May Protests

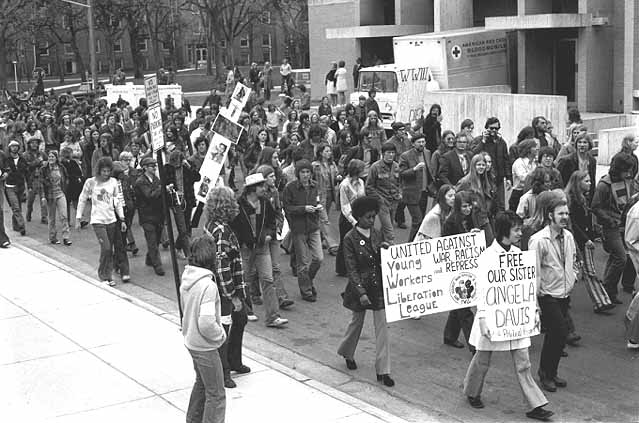

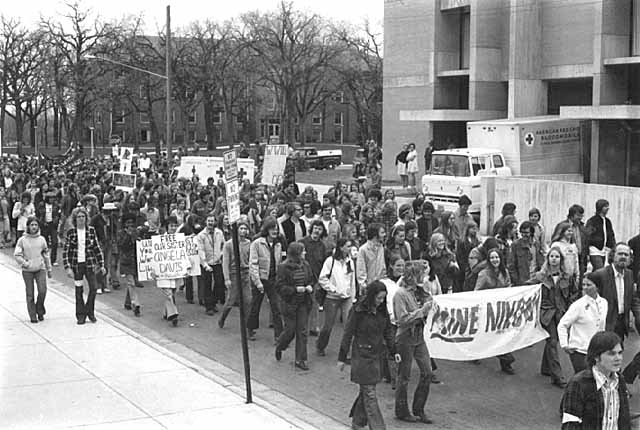

For many at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities campus, May 9, 1972 started out like any other day. The weather was much cooler than normal, so students rushed to and from their classes. The buzz on campus concerned President Nixon’s announcement that the United States would lay mines in North Vietnam’s Haiphong Harbor in an attempt to impede the supply of weapons and material to the North Vietnamese military. Later in the day, a rally against the mining was planned, along with an off-campus demonstration at the Cedar-Riverside housing development’s opening ceremony. Tensions were low on campus. However, the next few days would turn into the most turbulent in the University’s history. The rally against the mining of Haiphong Harbor was scheduled to take place at noon in front of Northrup Memorial Auditorium on May 9th. More than 250 students and faculty attended the peaceful, but enthusiastic demonstration. About ten University police officers were on hand in case of any disturbance. Meanwhile, there was a mounting concern that this group of demonstrators would meet up with a group protesting the opening of the nearby Cedar-Riverside housing development. The combined unease could lead to an unmanageable situation for University police officers.

United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development George Romney was scheduled to speak at the dedication of the housing development at 2:00 p.m. About 500 demonstrators, including some from the earlier Haiphong Harbor rally, gathered to protest the development, but Romney was running late. As they attempted to confine the protesters to the sidewalks, Minneapolis police officers were met with a volley of eggs, marshmallows, and rocks. Police charged into the crowd, swinging nightsticks and using mace on the demonstrators. Seventeen protesters were arrested for breach of peace and disorderly conduct. By the time Romney finally arrived at 5:00 p.m., the crowd had disbursed. In an attempt to not reignite the protest, the opening ceremony was held privately with only Romney and various Minneapolis city officials in attendance.

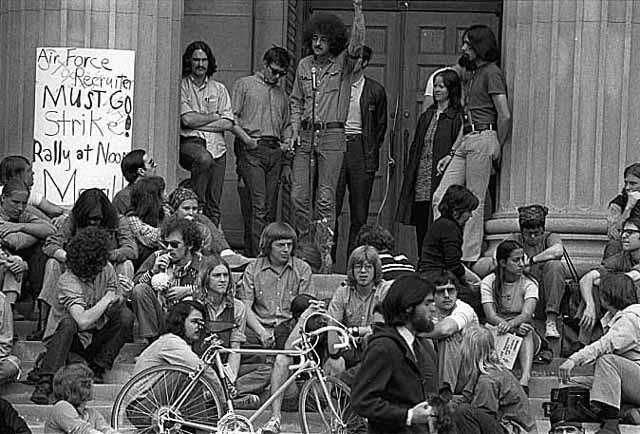

Word of another anti-war protest spread quickly across campus the morning of May 10th. The schedule for the protest included a noon rally at Morrill Hall, followed by the occupation of the Air Force recruiting office in Dinkytown. More than 1,500 protesters attended the rally, but only 800 moved toward Dinkytown afterward. When the protesters arrived at the recruiting office, they found that the Air Force had vacated it earlier that morning. Frustrated, the protesters moved toward the Armory, which housed the University ROTC. The crowd swelled to nearly 3,000 and filled three and a half blocks of University Avenue. Protesters began chanting “One, two, three, four, we don’t want your fucking war” while tearing down fences to make a barricade. Nearby, several members of a fraternity turned over an old car causing gasoline to leak onto the street. Within seconds, flames burst into the air. Rumors began to spread that the crowd was planning to set fire to the Armory. For University officials, it became apparent that this demonstration was beyond anything they had seen before and asked the Minneapolis Police Department for assistance in controlling the chaos.

Throughout the afternoon, communication problems plagued the University and Minneapolis police. Unsure of who was supposed to take the lead, Minneapolis police stepped up and took a stand in the most visible places as a show of force. Protesters always had a good relationship with the University police, but the demonstrators didn’t trust the Minneapolis Police Department. Their show of force backfired when the crowd erupted with shouts of “Seig Heil”. The demonstration was quickly spinning out of control. Minneapolis police began using their batons and mace to push the demonstrators away from the Armory. Undeterred, the protesters regrouped near Washington Avenue and Church Street and then split into two groups with the second moving to occupy Washington and Oak Street. Their plan was to stop business as usual and divide the police force between the two groups. Again, police rushed into the crowd, clubbing protesters and spraying them with mace. The protesters split again, this time occupying Northrup Mall and a large section of Dinkytown. In a final attempt to disburse the crowd, a police helicopter sprayed tear gas down on the protesters. The gas was only minimally effective on the crowds due to gusty winds but did wreak havoc on innocent people throughout Dinkytown and Stadium Village. Elementary school children walking home were exposed to the gas and University Hospital was forced to close all of their windows in an attempt to keep it out of patient’s rooms.

Once the gas cleared, demonstrators began tearing down fences and gathering debris to build a massive barricade to block Washington Avenue at Church Street. The crowd’s hatred of the Minneapolis police had reached a boiling point. University officials felt that the only way to calm the crowd was to put a stop to the Minneapolis police from clubbing and gassing the protesters. It was time to ask Governor Anderson to bring in the National Guard.

When the National Guard arrived on the scene at 1:00 a.m. on May 11th, the crowd calmed. About fifty protesters stayed at the barricade while others slept in Coffman, which the Student Association President declared be open to protesters. Governor Anderson recalled that the Minneapolis Police Department found it difficult to empathize with the protesters, but members of the National Guard were able to identify with them and understand their motivations. The Guard’s arrival became a turning point in the demonstrations. There was no more clubbing, mace, or tear gas. Before the Guard arrived, there were thirty-three arrests and twenty-seven protesters and police hospitalized with injuries. Afterward, there was only a handful of arrests and no injuries.

Protesters were still in control of Washington Avenue on May 11th. Meanwhile, over at Coffman, a crowd of 6,500 gathered at a rally that featured U.S. Senator and Minnesota native, Eugene McCarthy. McCarthy was met with a mixed reaction from the crowd. Some supported him as the peace candidate for President in 1968 while others jeered him as a man who voted to extend the draft. The tension on campus simmered throughout the day. Isolated fires and explosions, and rumors of escalating violence kept students, faculty, and administrators on edge. Demonstrators continued to hold the barricade on Washington Avenue throughout the day. Another group blocked both the east- and westbound lanes of I-94 for about 45 minutes before the police disbursed the crowd. At the same time, University and Minneapolis police and the National Guard watched as battle-tested students from universities such as Madison and Ohio State, filtered in to join the protest.

On the morning of May 12th, only about 150 protesters remained at the barricade. Within five minutes, police disbursed the crowd with no arrests or injuries and dismantled the barricade. For the first time in five days, no new disturbances were anticipated. Protesters quickly planned and carried out another rally at Coffman. As the crowd grew to more than 4,500, a police helicopter began circling overhead causing the demonstrators to be on edge. While the protest leaders argued over strategy, a University official pushed his way to the top of the Coffman steps. In an attempt to quell another violent clash between police and protesters, he announced that the National Guard would begin clearing the crowd if they didn’t disperse within twenty minutes. Tensions eased, and most of the crowd left. About one hundred protesters moved toward Ford Hall to built another barricade. That evening, the National Guard left campus.

The Ford Hall barricade fell on May 13 without much resistance from protesters. Further attempts on May 13-15 to demonstrate and organize against the war failed to sustain the momentum of the earlier protests. The last demonstration of May 1972 took place on the 16th. Less than one hundred demonstrators occupied Johnson Hall for three hours before leaving under threat of police intervention.

By June, most of the protesters who faced trial had their charges dropped or received small fines. A Hennepin County Grand Jury was convened. They criticized the Minneapolis Police Department for breaking ranks with University Police, using their nightsticks on demonstrators without intent to arrest or detain them, and overall demonstrating poor judgment throughout the protest. The department was further chastised for spraying tear gas from a helicopter and harming innocent bystanders in the process. The Grand Jury also admonished the University for not responding quickly enough to the violence. Meanwhile, the public supported taking a tough stance against the protesters. Nearly 80% of Twin Cities residents found the demonstrators more responsible for the violence than the police. Almost 75% of the people polled agreed that those involved in the demonstrations were concerned with nothing more than creating chaos.

The Eight Days in May protests were the last major anti-war demonstrations at the University and part of the last wave of protests nationally. U.S. military involvement in Vietnam wound down and finally ended in January 1973. After several years of unrest because of the war, the University of Minnesota campus was finally quiet.