Buchanan: A Town of Firsts

Rumors of copper riches hidden in the North Shore’s streams and hillsides had excited the imaginations of mineral prospectors and speculators for years. Copper towns were numerous along the North Shore of Lake Superior in the mid-19th century. With few exceptions, the town sites, much like their creators’ dreams, never became a reality.

In 1856, Buchanan was established as the seat of the U.S. Land Office in the northeastern land district in Minnesota Territory. The founders of Buchanan had high hopes of creating a boomtown — they believed there was a lot of copper in the nearby bed of the Knife River. The first settlers expected Buchanan to eventually become the capital of the county and the greatest copper port in Minnesota. Along with the perceived mineral seams, a seemingly endless supply of white pine and fur-bearing animals all around, and the close proximity to the port of Duluth seemed to make this an ideal place for a town.

It wasn’t long before a hotel, several saloons, boarding houses, a steam dock, residences, and buildings for the post office and newspaper office sprang up in Buchanan. All of the buildings were likely constructed with logs from the forest along the shore. An early copper prospector described that “Timbers were taken out, nicely hewn for five two-story buildings in town.” Two of these buildings were used by the land officers while the others served as a hotel, boarding house, and saloon. When men ventured out of the wilderness and into Buchanan, they typically were looking for three things; provisions, a saloon, or the temporary companionship of a woman.

The streets were nothing more than mud paths, but the town did have a substantial dock on the lakeshore. Lake steamers made regular stops with equipment, provisions, and pioneers looking to stake a claim. The community had to bustle, anyone wishing to settle legally and explore or exploit the vast northeastern Minnesota district had to first file a claim at Buchanan. At its peak, the town encompassed 315 acres. Buchanan was also a town of firsts: it boasted the first ever post office in the northeastern part of the state, and was home to the North Shore Advocate — the first newspaper published on the north shore.

Through the latter part of 1858 business slowed at Buchanan and money, which had never been as abundant as its rich dreams, grew scarce. An economic panic and depression swept the nation shortly after the land office opened in 1857, and its effects reached as far as the wilderness surrounding Lake Superior. Although copper rumors continued and traces of the blue-green metal were found all along the North Shore, few if any got rich mining it. Copper fortunes were never found, and the economic depression still gripped the nation throughout 1858. Soon, claims cabins all up and down the north shore were abandoned. Buchanan was feeling the pinch. By May 1859, the Land Office reported only 46 32/100 acres had been sold for cash during the previous four months.

On June 26, 1859, the federal land office was relocated to Portland Township (which later became a part of the city of Duluth). What little commercial life was left in the north woods congregated in Duluth and Superior. Buchanan had become a ghost town, and its regression back to wilderness was swift. The town’s first fatality was the steamboat pier that was claimed by the breaking spring ice. Many cabins stood empty, inhabited only infrequently by local Native Americans, prospectors, and loggers. Eventually, all of the buildings were destroyed by fires that frequently swept the forest in the wake of excessive logging. Whatever the means, nature quickly reclaimed all traces of Buchanan. The process was so fast and so complete that historians have disputed the townsite’s location, appearance, and some even argued whether Buchanan existed at all.

Leonidas Merritt provided one of the only written descriptions of Buchanan in 1914. Merritt was one of the Seven Iron Men — the iron-ore pioneers of the Mesabi Range. He arrived in Superior as a child in 1856 and spent most of his life exploring and exploiting the region’s natural resources. From the memory of his youth he wrote, “Not many may know that in 1856 and 1857, on the North Shore of Lake Superior, just this side of Knife Island, was located a pretty little city called Buchanan, at that time the emporium of the North Shore, with a pretentious hotel, kept by one George Stull, the United States land office, steamboat docks, several saloons, boarding houses, etc. The town was abandoned soon after Minnesota was admitted to the Union. The several homes and business places mentioned stood for many years tenantless and intact, until finally destroyed by forest fire.” Merritt’s short recollection is one of the most complete accounts of Buchanan available.

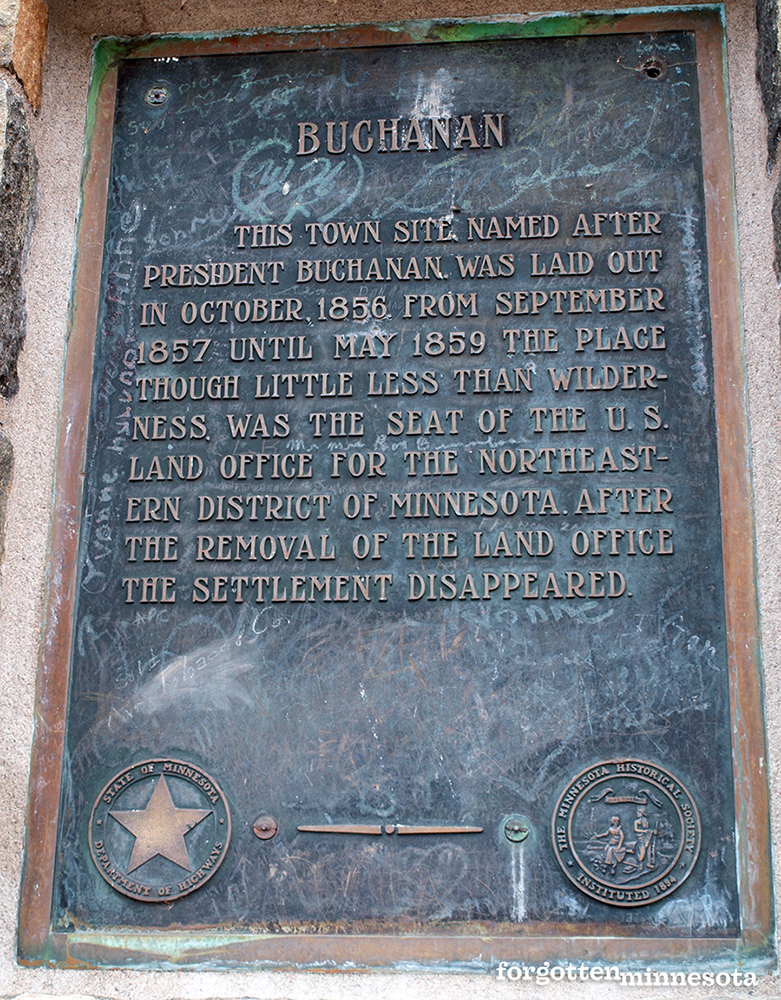

Today, nothing remains of Buchanan except a marker along Scenic Highway 61 between Duluth and Two Harbors. Even the marker’s placement is shrouded in mystery — is this truly the place where Buchanan once thrived?