FEMCO Farms: The Birth of Diversified Farming

Frederick E. Murphy was known as the publisher and guiding spirit of the Minneapolis Tribune newspaper in the 1920s and 1930s, but it was his commitment to agriculture in the upper Midwest that received worldwide recognition. He was touted nationally as an advocate for identifying problems in the business of agriculture and promoting sound, common-sense solutions to the issues that farmers were facing in the first half of the 20th century. His ideas around diversification in farming caught the attention of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who personally selected Murphy to represent the United States at the world economic conference in 1933 and 1934.

In 1918, Murphy’s brother William traveled to Chicago for business and contracted Spanish Influenza. He died there suddenly and without expressing his final wishes about how his heirs should address the newspaper and affiliated businesses that William owned. Shortly before the death of his brother, Murphy left the newspaper business due to his own health concerns. He moved to a farm near Breckenridge in western Minnesota with his wife Katherine.

Murphy’s life-long interest in agriculture stemmed from growing up on a farm in Wisconsin. He saw first-hand how a farmer’s livelihood depended on high yields from a single crop. Murphy set his mind to exploring modern ways of improving the economics of agriculture while he was on the farm near Breckenridge. For the next three years, he experimented with crop rotation and finding cash crops that could rival wheat in production and revenue.

In his opinion, the problem was simple. Farmers were far too dependent on one cash crop—wheat. Because they were only paid after the harvest, their entire yearly income depended on a high-quality yield and a favorable market.

Murphy believed that the solutions to these problems consisted of persuading farmers to improve their operating practices in an attempt to produce better products with higher yields as a means of increasing revenues. He would provide farmers with scientific methods to raise and diversify incomes through crop rotation and the introduction of livestock. Livestock would create income for farmers all year through the sale of dairy products, eggs, meat, or wool. The waste from livestock could be used as fertilizer that would help to restore the quality of the worn out soil. If done correctly, farmers would face only minor inflation in expenditures of time, labor, and cash.

During Murphy’s sabbatical from the newspaper business, he took charge of the farm in Breckenridge and implemented these ideas in an attempt to prove that diversification, crop rotation, and fertilization were the way of the future. He would eventually purchase additional farms to add acreage and livestock.

In 1921, William’s estate was settled and Murphy became the publisher and president of the Minnesota Tribune Company, which included the newspaper and its affiliated businesses. Murphy and his wife moved back to Minneapolis to guide the day-to-day operation of the newspaper. Being 200 miles away from the farm meant that he needed trusted assistants to maintain the operation. He continued to direct the activities and expansion of the farm through the mail and frequent visits to the Red River Valley.

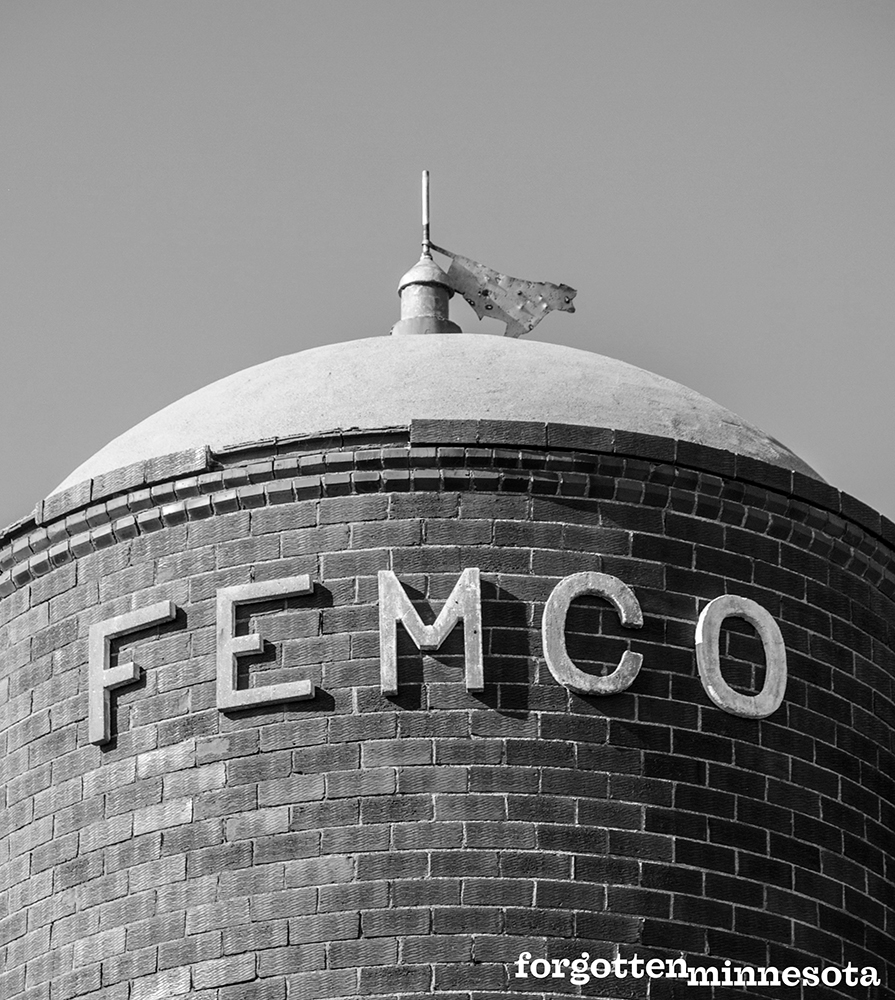

The Tribune acted as a vehicle for Murphy to influence and promote his ideas for better and more profitable farming methods, as well as boast about the farm’s successes. This influence, together with his eagerness to modernize the business of agriculture, led Murphy to establish the Frederick E. Murphy Company (FEMCO) farms in 1921. The operation would quickly grow to include a network of six farms and more than 6,000 acres. FEMCO farms allowed Murphy to put large scale, modern ways of making agriculture more profitable into practice in an attempt to provide farmers with the direct evidence of what could be accomplished by raising livestock, rotating crops, and fertilizing the soil.

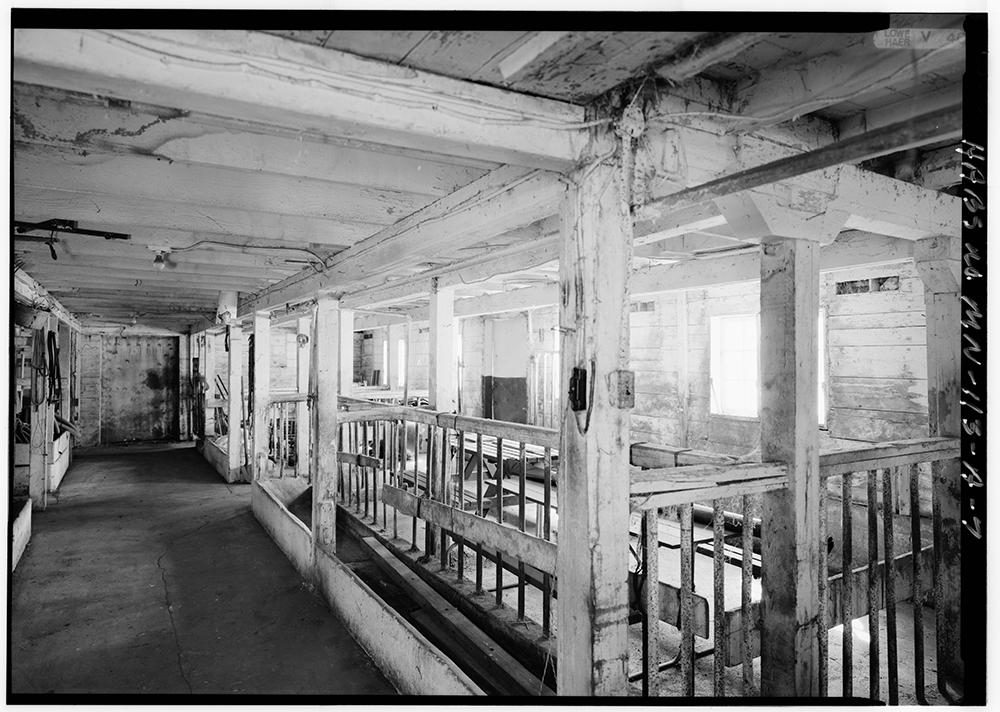

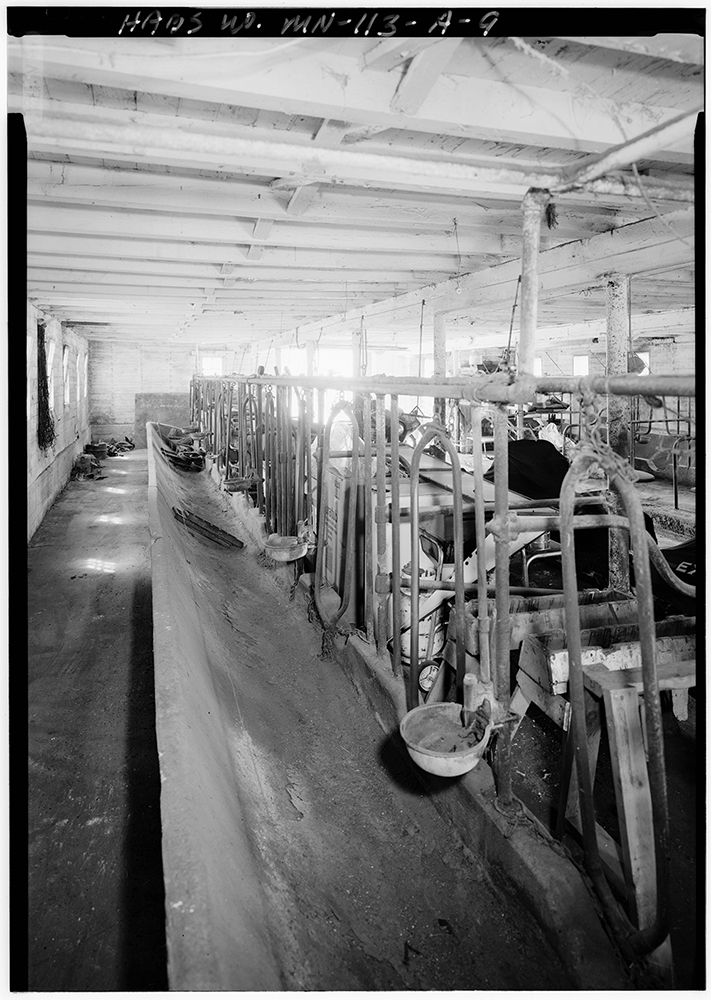

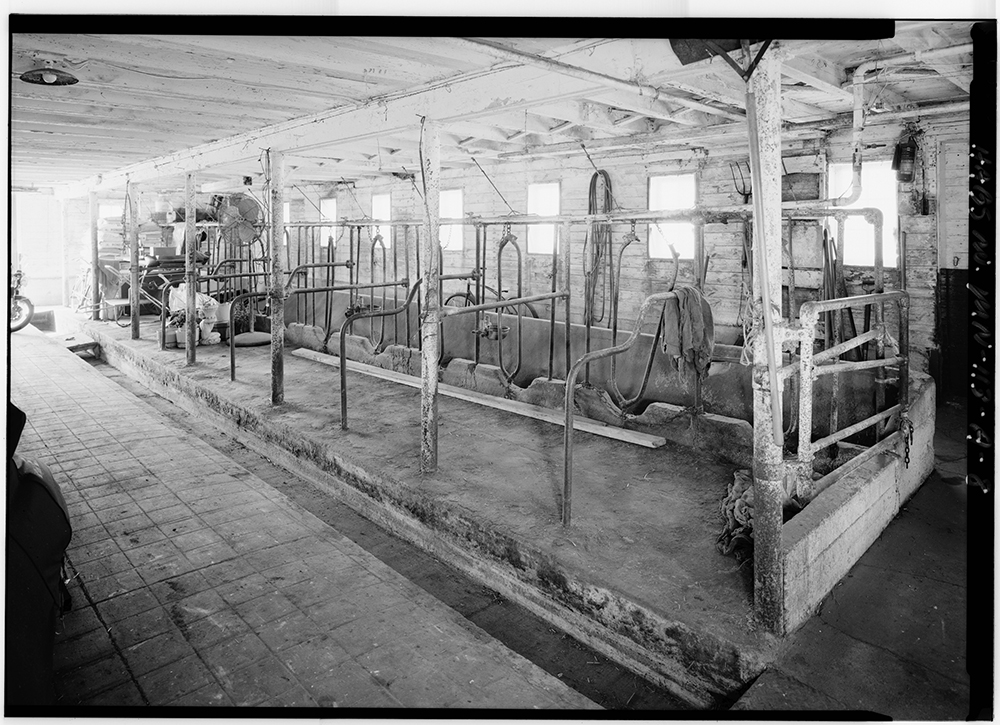

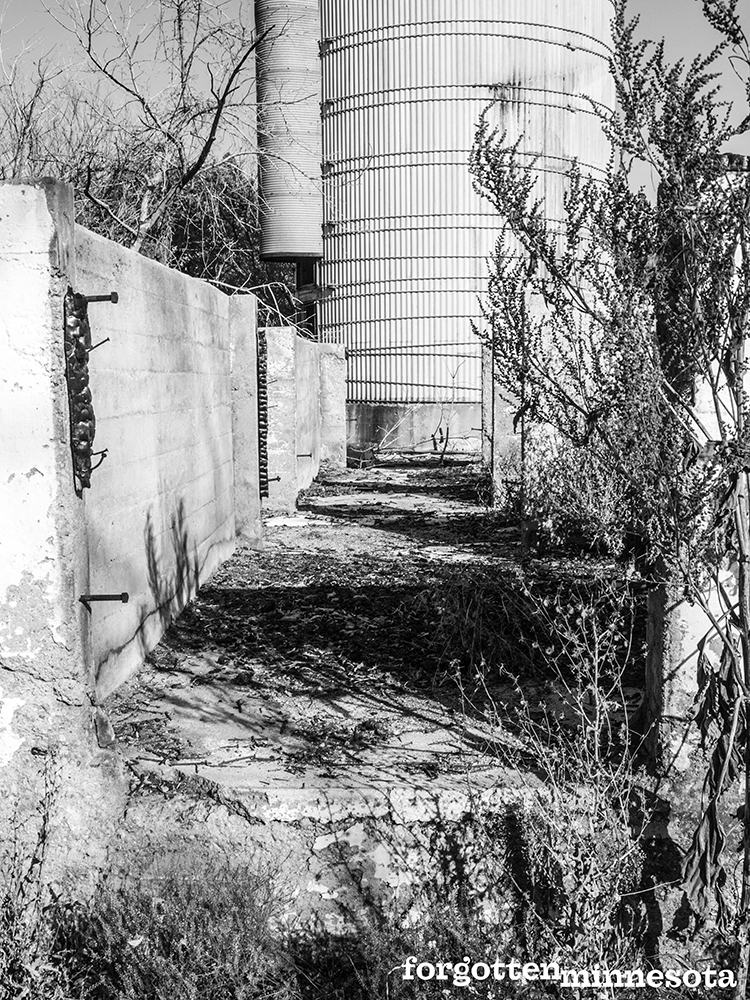

FEMCO farms number one and number two acted as the hub of the operation because they were the largest and most diversified. The layout of these farms was very similar. The complex of buildings included a two-story farmhouse used by the foreman, a small house for Murphy, a drive-through granary, milk house, dairy barn, double concrete silos, hog barn, sheep barn, horse barn, machine shed, chicken coop, and a windmill. Both farms originally consisted of around 1,200 acres each.

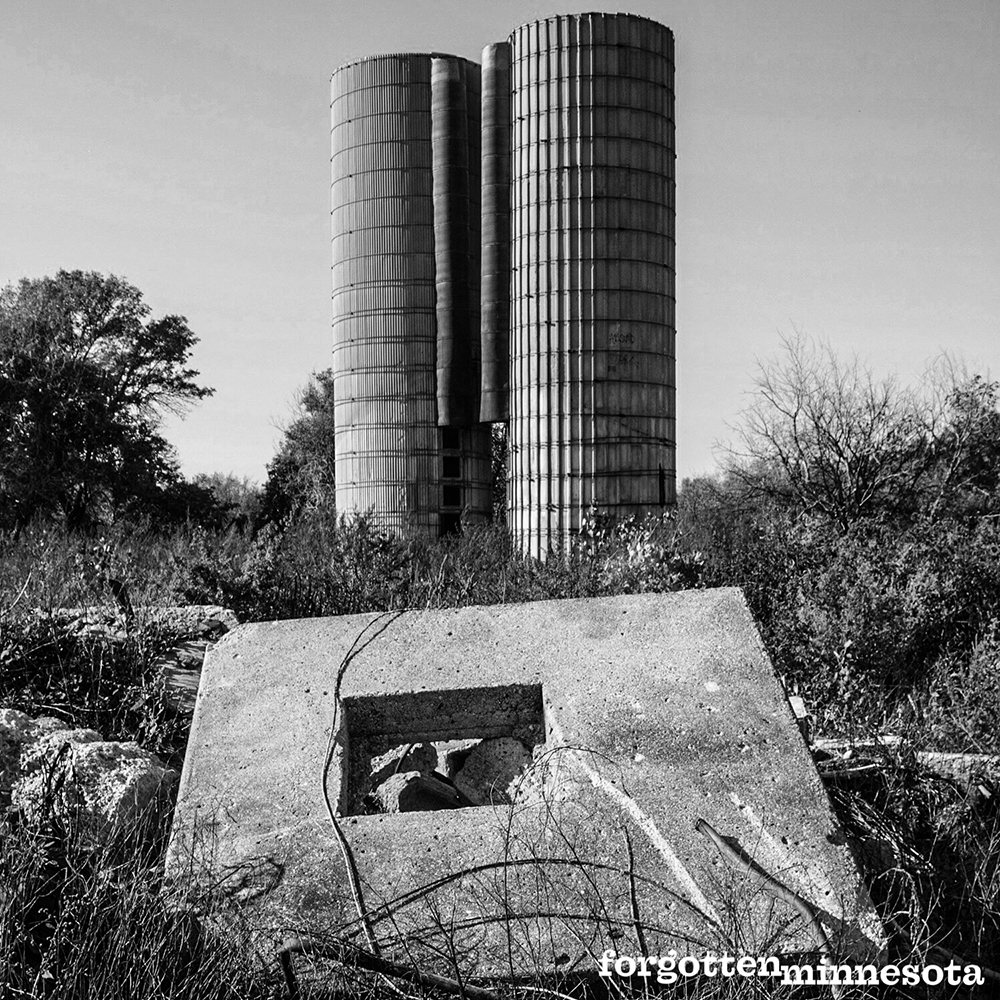

FEMCO farm number one was the original farm and the birthplace of Murphy’s diversified farming experiment. Located off of Highway 75 in Connolly Township, this farm had one of the largest A.C.O. tile silos ever built. A.C.O. silos were constructed with curved blocks made of burned clay, iron, and cement that are cut angular to make the interior and exterior smooth. At FEMCO, twin silos with a common chute were built in 1930 using this method.

Located in nearby Roberts Township, FEMCO farm number two was constructed in 1922 and strongly resembled farm number one. Farm number four was a small farm with only a few buildings located just north of farm number one. Farm number three was located in Mitchell Township, number five in Manston Township, and the manager’s farm near Breckenridge.

Murphy hoped to convince farmers that oats, corn, and barley together with alfalfa, sweet clover, and other feed crops should be included on every farm in the state to alleviate the financial burden that traditional cash crops—such as wheat, rye, and flax—put on farmers and their families. Unlike some others who were experimenting with diversification, Murphy never advocated for abandoning cash crops altogether. Instead, he stressed crop variety. Adding forage crops would help restore and maintain the soil fertility needed to improve yields, and provide livestock with food throughout the winter. Products produced by livestock could be sold year-round, making once-per-year payouts a thing of the past.

Through many trips to national agricultural shows, state and county fairs, letters from civic leaders, and countless conversations with his neighbors in western Minnesota, Murphy began to understand that asking farmers to make changes to the way they do business would be more of a burden than many farmers could take on financially. He recognized the need to help farmers secure loans for the purchase of registered livestock and quality seed. When the banks in the Twin Cities weren’t able to provide enough financial assistance to farmers wanting to diversify, Murphy enlisted capital from the east coast to fill the gap. The result was the formation of the Agricultural Credit Corporation (ACC). The ACC was funded with $10 million of privately-subscribed capital that gave the corporation the power to borrow up to $100 million more from the War Finance Corporation in the 1920s.

With a total of $110 million available for farm assistance, farmers were able to receive support when they were ready to diversify and modernize their operation. The ACC loaned more than $3 million for purchasing purebred cattle and sheep between 1924 and 1928 alone.

FEMCO farms became well known for their development of foundation herds of livestock from which other farmers could purchase offspring to improve their dairy operation. The stars of the entire enterprise were a renowned herd of Holstein dairy cattle. It was recognized nationally as the largest and finest herd in the country and continually produced cows that shattered production records. The herd was so important that barns unique to FEMCO were designed for them. The arrangement consisted of two large gamble-roof barns connected by a one-level, gamble-roof vestibule. The U-shaped center was then fenced to create a cattle yard that kept the animals from roaming too far from the barn.

Although the Holsteins were widely celebrated, FEMCO was also known for their award-winning Duroc-Jersey hogs, White Orpington chickens, and Shropshire sheep that again served as foundation stock. America’s finest studs of imported Percheron draft horses were also raised and maintained on the farms.

The grain husbandry program at FEMCO proved that proper planning was essential for good farming. Murphy promoted his idea that extensive preparation of seed beds by deep plowing and intensive field work was a necessary foundation for good quality seed and crop rotation. He proved it by producing better quality wheat, corn, rye, oats, barley, and alfalfa with higher yields than anyone else in the region.

Under Murphy’s watchful eye, FEMCO farms thrived through the difficult modernization era and the Great Depression. They served as inspiration for other farmers and economists alike. Sadly, Murphy died of a heart attack during a coughing spell on February 14, 1940. He had been confined to his hotel room at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York for two weeks with a cold before his death. News of his passing spread nationwide. His widow received messages of sympathy directly from President Roosevelt, the secretary of state, many members of Congress, owners and editors of national and local newspapers, and several agriculture groups.

During a press conference on the day after Murphy’s death, Minnesota Governor Harold Stassen stated: “The history of Frederick E. Murphy is that of a man whose stature will grow as the years pass on. His was the touch of the builder. He used his power and influence in promoting sound development of the territory. His contributions did not consist of criticism or objections, but rather that of genuine, constructive work.”

Murphy and his wife never had children, and although William Murphy’s two sons were active in the newspaper side of the business, they didn’t want to oversee the farming empire that Murphy built. Soon after his death, the livestock at FEMCO was auctioned off. The bulk of the Holstein herd—204 heads—sold for $81,804. One top butter producer, a two-year-old female, went for $4,000 alone. A 172-head herd of FEMCO purebred shorthorn cows sold for close to $130,000—the top bull of that herd sold for $7,600.

In the end, the crowning achievement of the FEMCO farms was a far-reaching program that demonstrated what modern methods of farming could accomplish. Their formation and development were Murphy’s greatest contribution to the overall welfare of agriculture in the United States. Closer to home, Minnesota became one of the most diversified farming states and a leader in the dairy industry. A significant amount of credit for that rests on the shoulders of Frederick E. Murphy.

Today, fragments of the FEMCO farms can still be found in Wilkin County. The nearly original FEMCO farm number two was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 because of FEMCO’s lasting impact on the agricultural history of the United States. The complex of buildings at farm number one was demolished around 2014, but a few hints of the great farm remain. At the time of my visit, the silos still stood proudly along Highway 75. The few remaining buildings of the small farm number four were razed in the 1990s. Further information and structure status of farms number three, five, and the manager’s farm are unknown.