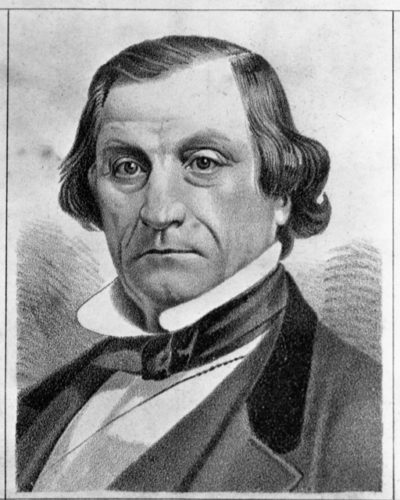

Joseph R. Brown’s Little Castle on the Prairie

Pennsylvania-native Joseph Renshaw Brown arrived in Minnesota at the age of 14 with the Army. He served as a drummer with the first troops assigned to build Fort Snelling in 1819. Brown remained at Fort Snelling until 1825 when he began trading with the Dakota. He opened his first trading post–a simple cabin–just outside the walls of the fort. After a few months trading at the cabin, he accepted a job as an independent trader with the American Fur Company and was sent to some of the most remote parts of the territory throughout the 1830s. In 1835, he met Susan Frenier, the daughter of a Dakota and Scottish mother and French-Canadian father. She was raised by her mother and stepfather at a Dakota camp near Lake Traverse. Brown married Susan the following year and they settled into a home and ran a small trading post on the St. Croix River. He named the settlement Dakotah. Later, Dakotah was named the county seat for St. Croix County in the Wisconsin Territory and eventually became part of the city of Stillwater.

Brown was appointed to several political positions over the following years. He played a central role in the 1846-1849 actions to establish the Minnesota Territory and served on the first central committee of the newly organized Democratic Party in Minnesota in 1849.

At the age of 48, Brown decided to change careers. He moved his growing family to St. Paul with Susan to become the editor at the Minnesota Pioneer. In 1855, he platted the town of Henderson–only the fourth town in Minnesota to be incorporated–and published a newspaper there from 1856-1857.

Changes came again for the family in 1857 when Brown served as the head of Henry Sibley’s successful campaign for election as the state’s first governor. Afterward, Brown played a critical role in formulating the state constitution.

By the end of 1857, Brown had been appointed by the federal government under Sibley’s recommendation to serve as United States Indian Agent to the Sioux (Dakota). Between 1857 and 1861 the family lived at the Upper Sioux Agency and Brown was responsible for activities at both the Upper and Lower Agencies.

After many years of living, trading, and forming three marriage alliances with the Dakota and Ojibwe. He was well suited to the job of Indian Agent and was liked and respected by the Dakota. In 1858, he led a delegation of Dakota leaders to Washington on a visit which resulted in the signing of the 1858 treaty in which the Dakota forfeited their reservation land on the north side of the Minnesota River. It was a move that Brown believed was inevitable but would be profitable for the Dakota.

Brown remained Indian Agent until 1861 when he was replaced by a Republican appointee, Thomas Galbraith, a man who had little experience with the Dakota and was unfamiliar and unsympathetic with their problems.

After losing his agency position, Brown chose a site on the north bank of the Minnesota River, seven miles southeast of the Upper Agency, to build a grand, stone house for his family. Construction began in June 1861. Brown’s only neighbors were a few settlers and traders living in isolated cabins, and the Dakota living in six settlements on the south bank of the river. Completed in just one year, Brown and his family lived in the house with several native and white employees including maids and a nanny.

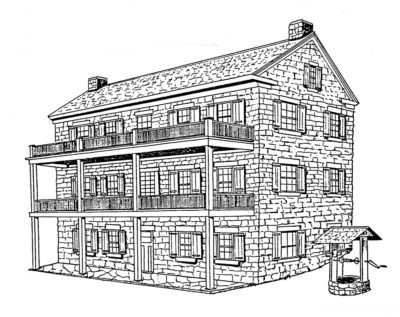

Brown’s granite castle

The Brown house was a three and a half story, 19-room granite castle. At 60-feet long and 30-feet wide, its size and opulence far surpassed the brick and wood-frame buildings at the nearby Upper and Lower Agency. The home was unlike any structure built outside of Minneapolis or St. Paul at the time.

Widely known as a friendly stopping place along the Minnesota River, the Brown’s home was often visited by travelers, officials, missionaries, and settlers. The family often held parties attended by houseguests, officers from Fort Ridgely, agency employees, and traders to provide glamour and formal social interaction on the isolated frontier.

Although no known photographs exist of the site, family members described it as being Federal or Greek Revival style with a gabled roof. It was built into a hillside with a first-story main entrance on the south side of the home, and another door on the opposite side that opened into the second story. The house is believed to have had 31 windows and a three-story porch spanning the entire length of the south side of the home. A pink-hued granite used on the exterior was quarried nearby.

Inside, the walls were finished with several coats of lime plaster strengthened with animal hair and tinted different colors in many of the nineteen rooms. The first floor had a central, eight-foot-wide main hall stretching the width of the house. A large kitchen and dining room were located at the front of the house, and four small storage rooms were situated along the back. Parlors, sitting rooms, and bedrooms were located on the second and third stories. The attic contained Brown’s office, complete with a billiard table and ornate wooden desk.

The home was heated with stoves instead of fireplaces. It was elaborately decorated with upholstered furniture, Damask curtains, bronze and crystal chandeliers, kerosene lamps, and modern cooking equipment. Many of the furnishings were purchased in New York City, shipped by rail to St. Paul, and then hauled to the house in wagons.

Trouble on their doorstep

The Brown’s had only been living in their new house for two months when the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 broke out. On August 18, 1862, two of Brown’s children visited the Upper Agency and were warned of trouble near the Indian village of Little Dog. Susan was home alone with her children while her husband was in New York City soliciting investors for his newest invention–a steam-powered wagon. The next morning, the entire household was awakened by a neighbor and friend of the Dakota pounding on the door of the home, urging them to flee at once.

Susan quickly gathered her 12 children, their hired help, and several neighbors and set off in wagons pulled by oxen toward Fort Ridgely. No more than six miles into their journey, the group was stopped by a group of Dakota. Susan is said to have stood on a wagon to defend the group by threatening the encroaching Dakota with the vengeance of her Dakota relatives. The Dakota allowed the men in the party to escape but took Susan and the other women and children to Little Crow’s camp where they were held for more than a month. Many believe this was done to protect Susan and her family rather than to hold them captive.

Brown returned immediately from New York and joined the volunteer force fighting the war in order to find his family. He was the commander of the scouting and burial party that was ambushed on September 2 in the 30-hour Battle of Birch Coulee and fought in the final decisive Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, 1862. Brown was reunited with his family at the mass release of war prisoners on September 26, 1862, at Camp Release.

Although the Brown family escaped injury, their house was set on fire and nearly all of their furnishings and personal possessions were destroyed or stolen. Among the items found in the home after the fire were fractured pieces of dishes and pottery made in England, metal parts from a piano, door locks, hinges and latches, a meat grinder, a broken skillet, iron kettles, a cooking stove, flatirons, brass candlesticks, thimbles and embroidery scissors, and a Singer sewing machine manufactured between 1858 and 1861. In the years following the fire, much of the stone from the walls and foundations of the house, stables, and root cellar were removed from the site by local farmers and used to improve their homes and barns, and to construct fences.

After the war, the Brown family moved to what would become Browns Valley in Traverse County. Brown served as a special military agent on the Minnesota-Dakota border and ran a trading post and stock farm. He died unexpectedly in New York City in November 1870 while on a trip to promote his steam wagon. Susan moved to the Sisseton Agency in South Dakota after Brown’s death to be close to her son, Joseph Jr. She died there in 1904.

The ruins of the Brown house were turned over to the Minnesota Division of State Parks in 1938. They conducted the first extensive archaeological excavations on the site and then stabilized the remaining foundation and walls in 1939. Another excavation, this time by the Minnesota Historical Society, took place in 1968 and expanded the collection of artifacts from the site. The Joseph R. Brown house ruins were placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986. Today, the site is a state wayside, complete with interpretive signs and picnic tables.