Mudbaden Sulphur Springs

In 1890, Ole Rosenthal and a friend were moving a cart across his property near the Minnesota River in Scott County when the cart got stuck in the mud. Believe it or not, both men were overjoyed when they noticed a strong sulfur smell coming from the mud that was being churned up as they tried to dislodge the cart. Stories about medical spas in Germany that used sulfur-rich mud to treat joint and muscle conditions were popular in newspapers across the county. If the stories were true, Rosenthal’s mud could be a proverbial gold mine.

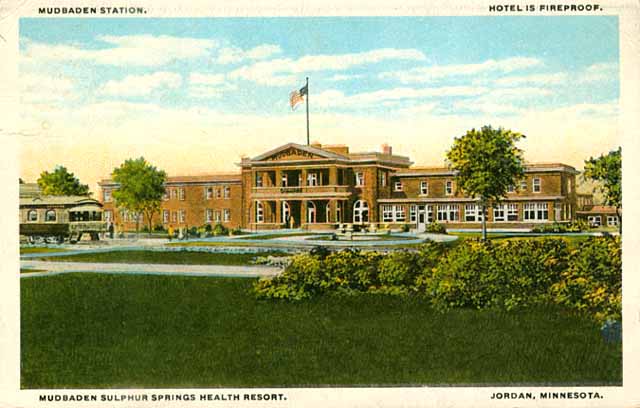

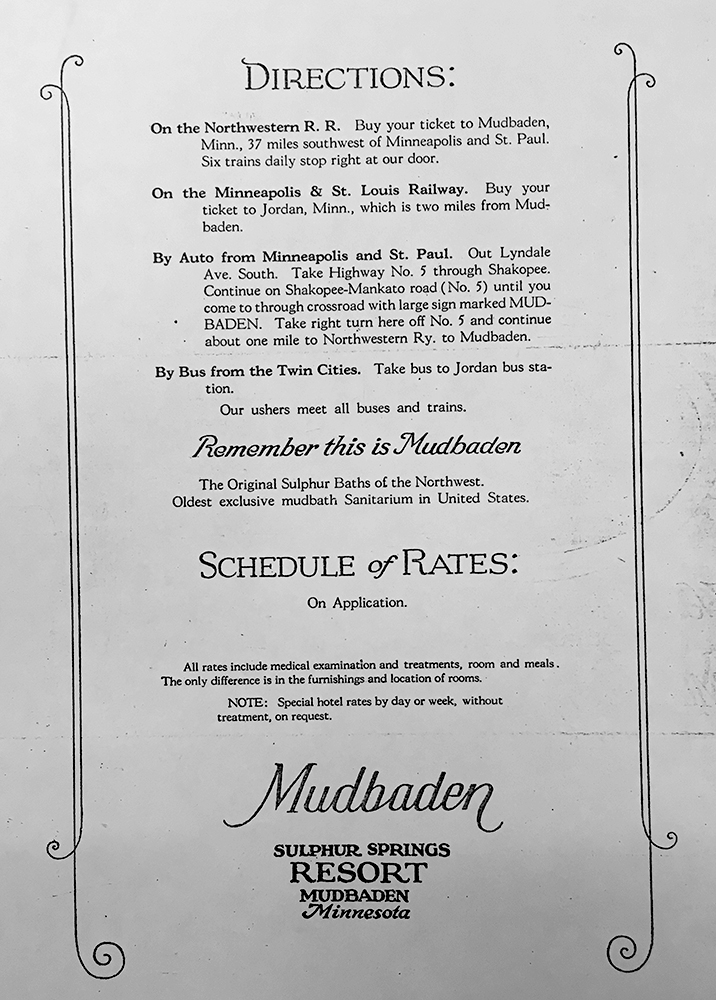

Rosenthal operated the Rosenthal Sulphur Springs treatment resort out of his home for several years. People came from all over the Midwest to steep away their aches and pains in hot mud baths. In 1915, a larger, two-story red brick Classical Revival style structure was built. This modern facility had a central section flanked by long narrow wings on each side. The treatment spa was renamed Mudbaden Sulphur Springs and catered to wealthy patients and tourists looking for a cure to rheumatism and other common joint and muscle conditions. People with chronic diseases, such as high blood pressure and liver disease, also sought treatment in the mud. The popularity of Rosenthal’s sulfur spa grew beyond what he could manage on his own, so he took on a partner for several years before eventually selling the operation.

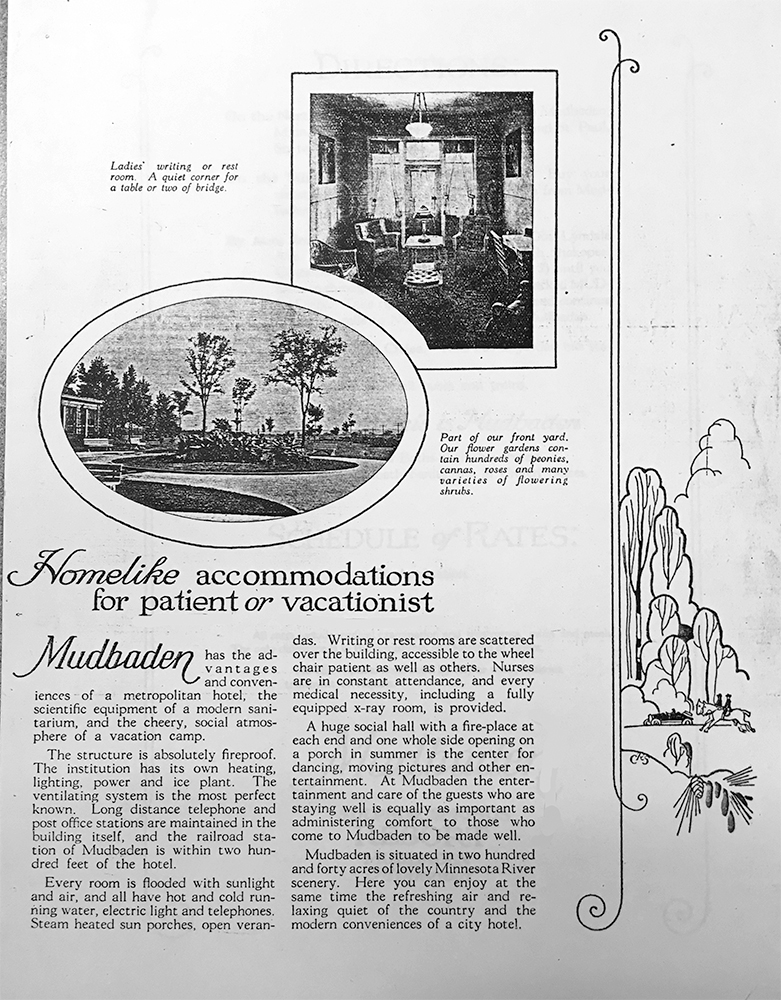

In its heyday, up to 125 patients could stay at Mudbaden and up to 200 could receive treatment. Trains would unload patients at a depot just steps away from the facility. Single and double rooms with sinks were located on the upper floor and a large communal dining room, gathering spaces, and treatment rooms were located below. Before an elevator was added to the building, patients could use a special stairway with steps only a few inches tall to navigate between their rooms and treatments.

Patients could receive treatment as little as once a day, or several times a day depending on the severity of their condition. During treatment, patients would lie on a metal slab covered with two or three inches of hot mud and then be covered from their toes to their necks with more mud and left there until the mud cooled. The rooms were stifling hot and notoriously smelly, so sulfur water was provided to keep patients hydrated.

The health spa operated until 1947. The property was taken over by a seminary before being sold again in 1970. It was used as an in-patient chemical dependency treatment center until 1985. Then Scott County acquired the property and turned it into a minimum-security jail. Thankfully, very few changes to the interior and exterior were made. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

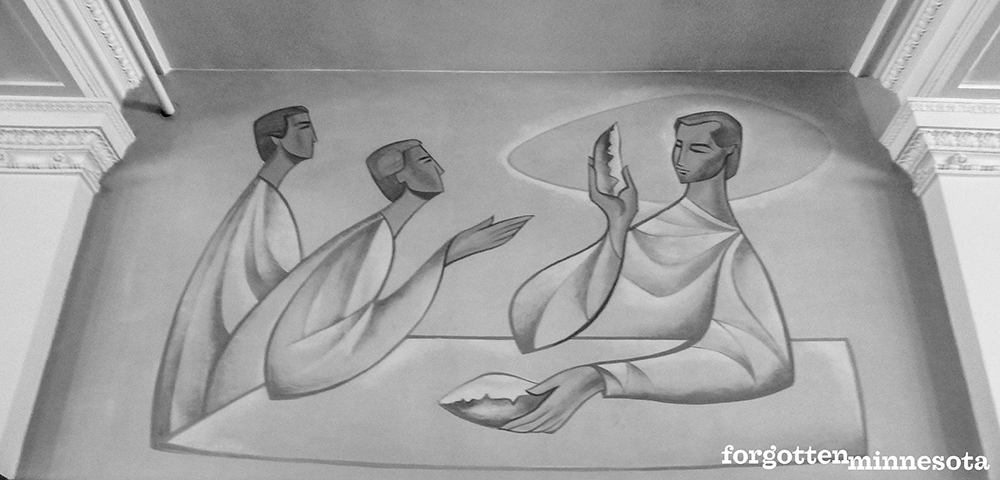

Today, SCALE (Scott County Association for Leadership and Efficiency) uses the building for public safety training for law enforcement, firefighters, and other public works groups. They value the history of the building, and have upgraded the building to meet code requirements, but maintained the historical integrity of the building.

I visited Mudbaden on a chilly day in March 2017 with a plan to grab photos and move on to the next place on my list. As luck would have it, Mike Briese from SCALE saw me taking photos and offered to give me an impromptu tour inside. It was clear that Scott County and the people who work at SCALE value the history of the building and are just as into knowing more about the past as we all are. Thanks again to Mike for the tour and chatting with me about Mudbaden then and now.