Pan-Town-on-the-Mississippi: Pan Motor Company’s Town

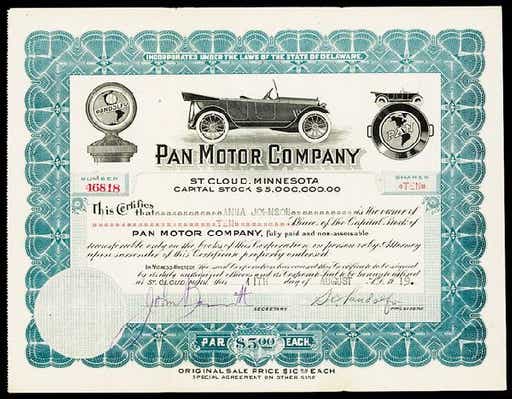

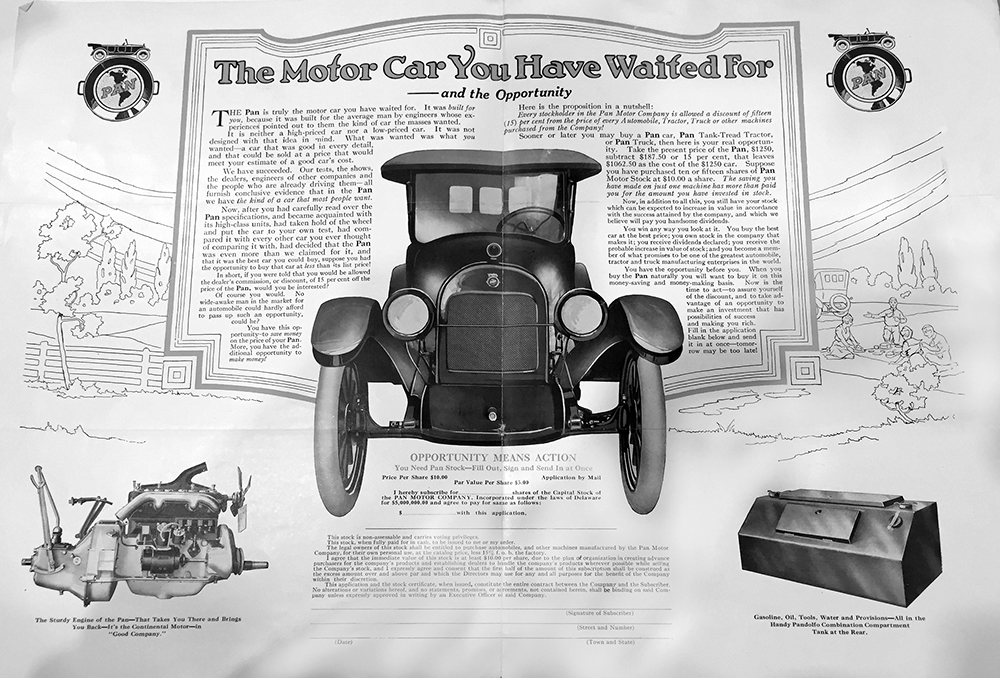

When Samuel Pandolfo arrived in St. Cloud in 1917, he dreamed of building an automobile empire that would rival Detroit. He chose St. Cloud because two rail lines already ran through the town, making it possible to receive supplies and ship his cars to the Twin Cities and then on to Chicago and points east. He also believed the farmers in the area would jump at the chance to get out of the fields and put their experience fixing and maintaining their farm equipment to good use by helping to design and manufacture automobiles. The people of St. Cloud welcomed him and his enthusiasm for building an extensive industrial and residential complex for the manufacture of the Pan Motor Car. In fact, many of St. Cloud’s elite purchased stock in the enterprise, and several local leaders became directors in the company.

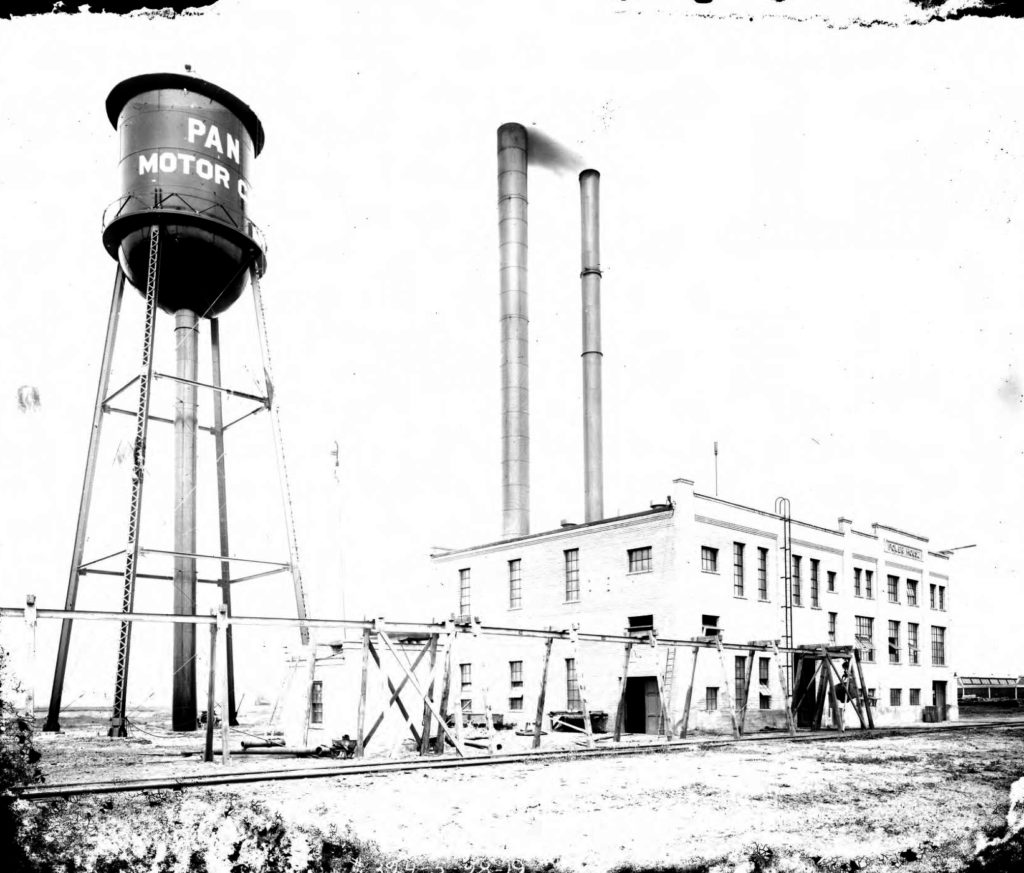

Pandolfo’s interest in automobiles began as he traveled around the southwestern part of the county selling insurance. He claimed to have worn out 37 cars in his time as a salesman in addition to suffering through numerous breakdowns and uncomfortable days behind the wheel. He believed this experience would put him in a unique position to manufacture cars that were comfortable, fun and efficient to drive, and outlast any vehicle currently on the market. After acquiring 47-acres of land, Pandolfo began construction on a factory for the manufacture of the Pan Motor Car and office buildings for the operation of the business.

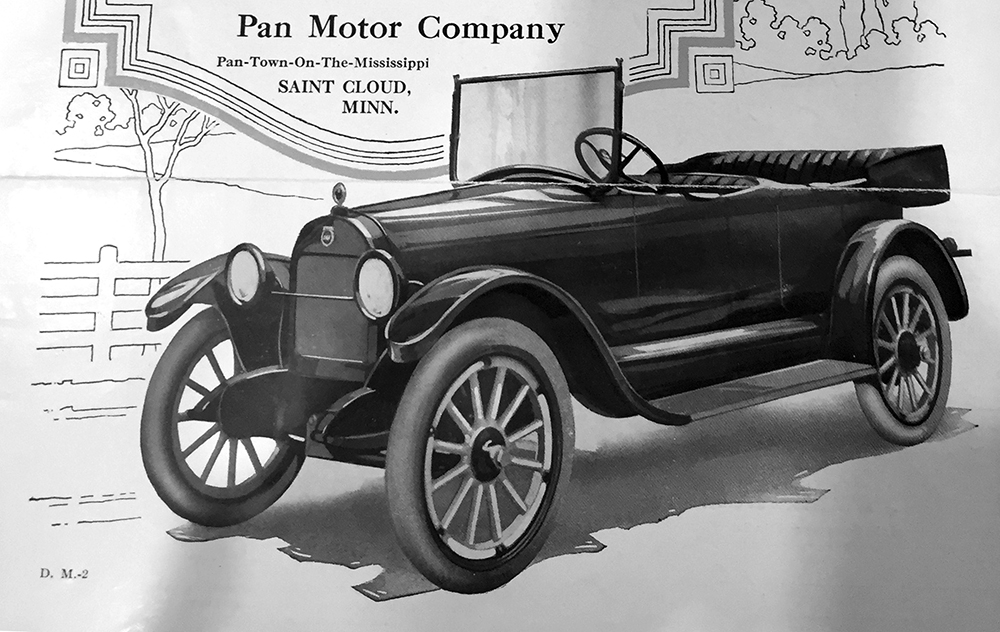

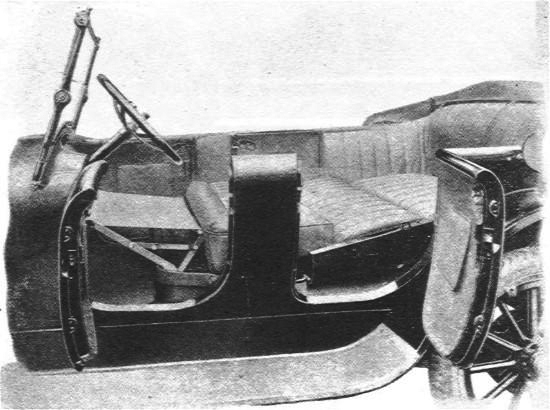

The first Pan Motor cars were considered touring models with contemporary bells and whistles. They included innovations such as a canvas roof that could easily be retracted, a gas gauge, built-in clock, a built-in icebox to keep snacks fresh, and an electric starter that heralded the end of the hand-crank starter. It was even possible for the seats to fold down and be used as a bed. To prove his cars were road-worthy, Pandolfo arranged an event in 1918 for the media and stockholders where three Pan Motor cars raced over rough roads to the top of Pike’s Peak in Colorado. Investors lined up to become part of the Pan Motor Company with Pandolfo as its ringleader and sales of the car began rolling in.

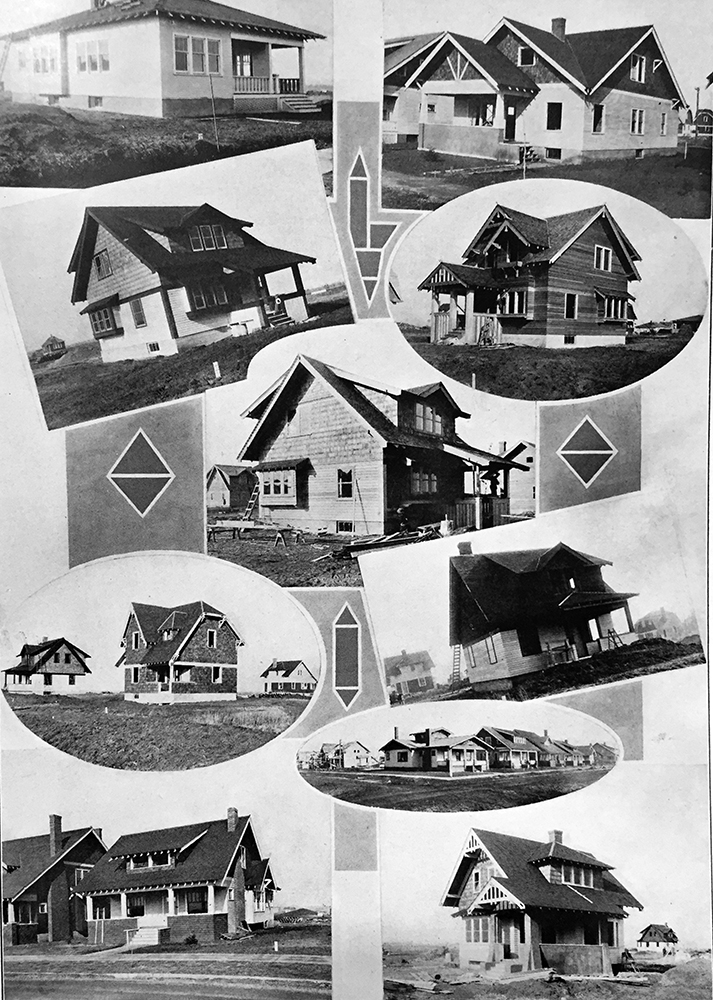

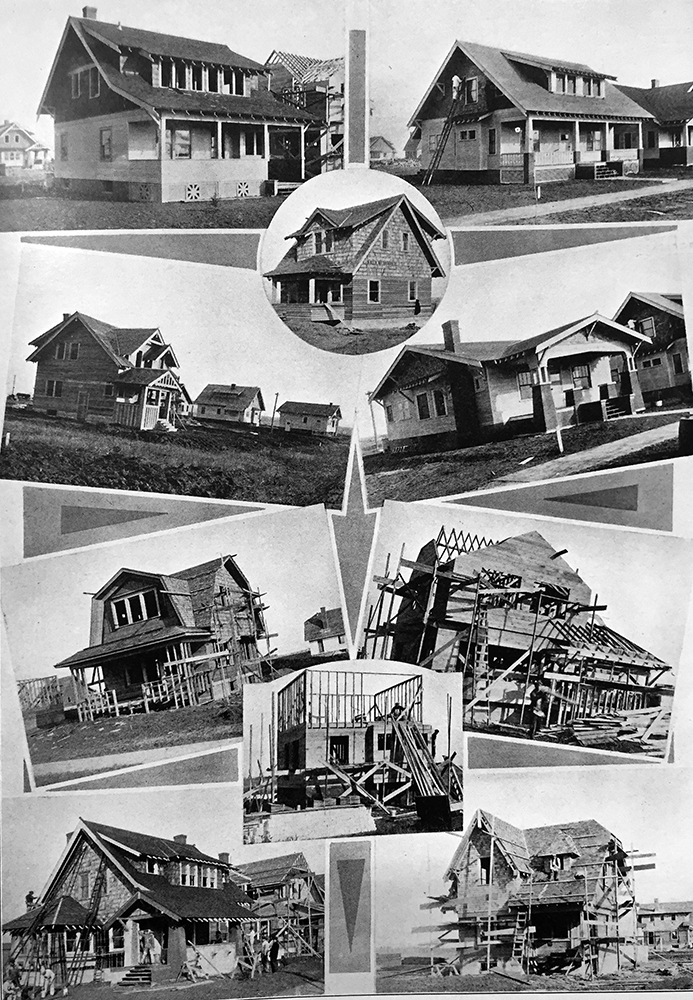

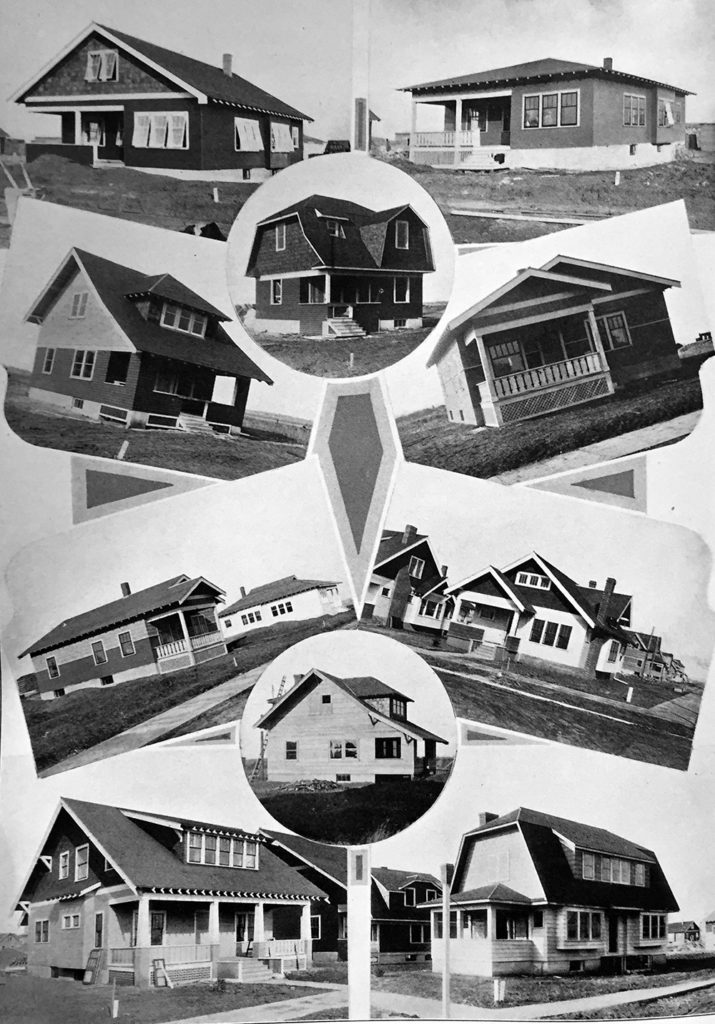

Once stockholders had contributed the capital needed and the factory was in place, Pandolfo began planning a company town to house the employees that would be necessary to keep up with the demand for his automobiles. To his credit, Pandolfo knew he didn’t want Pantown to resemble an ordinary company town with cheaply-made homes that all looked alike stacked onto each block as tightly as possible. Instead, he envisioned neat rows of bungalows with open porches and lawns for families to enjoy.

With that in mind, Pan-Town-on-the-Mississippi was born. Located in a six-block area in the northwest corner of St. Cloud, Pantown was built adjacent to the Pan Motor Company factory to make getting to and from work easy. Twenty-five house plans in the Craftsman and Western Stick styles were drawn up by architect Arthur C. Clausen to meet the needs of three categories of employees: executives, managers, and workers. All of the homes had maple flooring throughout with oak and pine used for interior millwork and trimming.

In 1918, local contractors went about building the homes in Pantown. Fifty-eight houses were built to house factory and office workers and their families. Even the most modest of the bungalow plans–featuring just one bedroom and bathroom, a living room, and an eat-in kitchen–were stylish with subtle detailing and plenty of room for a family. The character of the mid-range homes was enhanced with bow windows and wide porches. Meanwhile, Pan Motor Company executives lived in homes with eight or nine rooms spread across one and a half or two levels. Unmarried employees often lived in the 23-room housing complex that featured a common dining room, kitchen, and a lunch counter for bachelors who didn’t cook their own meals.

Pandolfo lived with his wife, Anna, and their two children, Vivian and Samuel Jr., in the first house built in Pantown–a one and a half story Craftsman-style home with bay windows, extended gables, and wooden window planters for flowers. Advertisements for the community boasted that “where in July 1917, there was nothing but prairie land, quack-grass, and jackrabbits, there stands today a community of homes and beautiful surroundings as if by miracle born. Velvety lawns have replaced the wiry prairie grass. Shade trees grace the boulevards, and shrubbery is in full bloom in the front and rear yards.”

The homes were only part of Pandolfo’s plan for Pantown. Modern street lighting with granite poles and 16-inch ivory globes around a 400 candle-power lamps were installed along with graded streets with curbs, concrete sidewalks, its own sewer system, and water supplied from an “artesian well sunk 150 feet” to make the neighborhood attractive for potential employees and their families. Pantown also had its own police force and a volunteer fire department with hook and ladder and hose trucks that could act quickly if there was a fire in the factory or at a home in town. There were also several lots intentionally left open that could later be built on as the need for more housing arose.

Between 1917 and 1923, Pan Motor Company manufactured about 750 cars in St. Cloud and was awarded several government contracts during World War I. Pan Motor cars were considered by many to be the best and most popular of Minnesota’s 16 automobile manufacturers. Meanwhile, national automobile magazines boasted that the Pan Motor car was one of the most innovating in the country, mainly because of its small motor. In 1918, the Pan Model 250 was one of the most popular new models of the Chicago National Automobile Show.

Unfortunately, Pandolfo’s natural exuberance and ability to sell stock in the Pan Motor Company was also his downfall. The Minnesota State Securities Commission began looking into the progress of Pandolfo’s venture–investors were starting to question whether they would ever see a return on their investment. Even the most faithful supporters in St. Cloud began to lose faith in Pandolfo and questioned where all of the money that had been invested was going. Not to be deterred, Pandolfo launched a media campaign to prove that progress was being made at the plant.

However, in November 1918, Pandolfo was indicted by a federal grand jury in Fergus Falls for “using the mail to defraud in the sale of stock in the Pan Motor Company.” The charges in that case were eventually dropped, but Pandolfo’s legal troubles didn’t end there. The federal government brought new fraud charges in Chicago against Pandolfo and thirteen directors of Pan Motor Company. After a trail some saw as a circus sideshow on account of the judge’s narrow vision in legal matters, Pandolfo alone was found guilty of seven counts of mail fraud; he was fined $4,000 and sentenced to 10 years in Leavenworth Prison. He appealed the decision, but the United States Supreme Court denied the appeal in 1923 by refusing to hear the case.

After serving two years in prison, Pandolfo was released and returned to St. Cloud. Rather than seeing him as a crook, the people of St. Cloud believed Pandolfo was a victim of a larger conspiracy by the Detroit automakers to keep hold of their consortium within the automobile industry. To prove their loyalty, a massive welcome home parade of supporters–including a marching band–met Pandolfo at the train depot in St. Cloud and escorted him to the Davidson Opera House where he was lavished with praise and given a monetary gift to help him start a new venture.

By the time the fraud case was settled in 1923, Pan Motor Company had failed. Pantown was virtually deserted, and in 1926, the entirety of Pantown was sold at auction for a mere $103,000. Pandolfo’s entrepreneurial spirit wasn’t hampered by his time in prison. Once he settled back in St. Cloud, he opened Pan Health Food Company, which only saw moderate success. Never one to stop chasing the next big thing, Pandolfo left St. Cloud for Alaska where he revived his insurance sales career. He died there in 1960.

Pandolfo himself has never been forgotten by the people of St. Cloud. After his death, Pandolfo asked to be sent to St. Cloud for burial, but his request wasn’t honored until 2011 when his descendants and members of the St. Cloud Antique Auto Club granted his final wish. Pandolfo’s remains were exhumed from his grave in Alaska, cremated, and sent to St. Cloud to be reburied as he wanted.

Today, the Pan Motor Company office and sheet metal works buildings still stand on 33rd Avenue N near 5th Street. The buildings were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. St. Cloud eventually grew to include Pantown and new houses were built on the lots left open for future development. Most of the Pantown homes remain, although a few have been altered to the point that they are not recognizable as part of the original district. Pantown is eligible for placement on the National Register of Historic Places as a residential district, but it has yet to make it onto the list.

References:

Dominik, John J., The legend of Sam Pandolfo : Minnesota’s Pan Motor Company and its legacy.

Nelson, Gary. The Pandolfo story: St. Cloud’s own auto, the man who made it, and the man who can tell the story”

”Information on the care and operation of the Pan Model A: Care and operation of the Pan Model A.” Pan Motor Company.

“Pan town on the Mississippi : where they are building a town to a town, and where the atmosphere sparkles with vim, vigor and vitality.” Western Magazine. Vol. 11, no. 4

Pan Motor Company. Company records, 1918-1919. Minnesota Historical Society.

Archives of the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

Additional photos can be found at the Pantowners website.